We spend nearly a third of our lives asleep. But why dedicate so much time to seemingly doing nothing?

Sophocles acknowledged sleep as “the only medicine that gives ease,” while Shakespeare in Macbeth described it as the “balm of hurt minds.” But before the 1950s, sleep was often regarded as little more than an intermission on the mainstage of life.

Today, sleep is better understood as a bustling backstage, and science is beginning to lift the curtain on the crucial actions taking place behind the scenes.

“There are a lot of active processes in sleep, and it’s not wasted time. It’s valuable time for systemic health,” says Brian Murray (MD ’95), a neurology professor at the Temerty Faculty of Medicine and an affiliate scientist with the Hurvitz Brain Sciences Research Program at Sunnybrook Research Institute.

Much of what we know about sleep and health comes from observing what happens when people don’t get enough slumber. It’s something Murray says he experienced “viscerally” in his long on-call hours in medical residency.

Being awake for 24 hours causes a level of cognitive impairment that’s similar to having a 0.10 per cent blood alcohol concentration — that’s well over Canada’s legal threshold to be charged for DUI. This impairment worsens with chronic sleep loss. And Murray notes that sleep-deprived people, like drunk drivers, “do not have insight into how badly they’re doing as they become progressively impaired.”

We don’t have to experience extreme stretches of sleeplessness to suffer serious effects. Studies show that getting less than seven hours of sleep each night increases the risk for a wide range of health conditions, including obesity, diabetes, hypertension, heart attack and stroke. In addition, it can also lead to mental health disorders, cognitive decline and dementia.

If you’ve been burning the candle at both ends, it’s possible to quickly pay down a sleep debt. Even one good night’s sleep can restore as much as 80 to 90 per cent of normal cognitive function, Murray says.

“But the real question is: Can you repair whatever immune damage has been done while you were sleep deprived? Have you recovered from the cardiovascular or metabolic stress of sleep loss? Maybe you have misfolded proteins that didn’t get cleared from your brain. It doesn’t hurt you this week, but cumulatively … it adds up.”

With advances in technology, scientists are only now beginning to scratch the surface of what’s happening in the brain during sleep, Murray says. Research combining genetic and neuropsychological data suggests that sleep plays a role in synaptic regulation, particularly in the pruning of irrelevant connections made during the hours in which you’re awake.

“There’s only so much synaptic real estate, so something has to give,” Murray explains. In sleep, the least relevant synaptic connections are washed away, “and the important stuff is relatively strengthened. So sleep seems to be less about learning and more about unlearning.”

“You can think of the glymphatic system as dump trucks removing the garbage that accumulates during waking activity,” says John Peever (PhD ’01), a professor and head of the Laboratory for Sleep Research at the University of Toronto’s Department of Cell & Systems Biology.

This potential explanation for the link between poor sleep and dementia is “elegant and important,” Peever says, adding that it requires further investigation and replication. “We need to dig deeper in this direction to understand what waste is really being cleared, where it comes from and where it’s going.”

A window into the aging brain?

Peever’s research focuses on the biology of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and how it can break down in

conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, REM sleep

behaviour disorder and dementia.

“We know from a whole suite of clinical work that the first thing that goes wrong in neurological disorders like Parkinson’s is REM sleep,” Peever says.

For example, with REM sleep behaviour disorder, the usual paralysis that inhibits a person from acting out their dreams does not occur, resulting in sometimes violent and exaggerated body movements during sleep.

The condition has turned out to be the best and earliest indicator of Parkinson’s disease, appearing long before other signs of cognitive decline. More than 70 per cent of patients diagnosed with REM sleep behaviour disorder go on to develop Parkinson’s or dementia within 12 years of their sleep diagnosis.

“REM sleep must be playing some sort of role in this process because that circuit is targeted first,” says Peever. “There is likely a biological function to being paralyzed during REM sleep.”

On the flip side, paralysis and other features of REM sleep intrude into everyday life for people with narcolepsy, who can experience a sudden loss of muscle control while conscious and vivid hallucinations when waking or falling asleep.

Examining REM sleep in early life, when the brain is most plastic, may provide clues to what’s going wrong. Newborns spend more hours asleep than awake, and time in REM sleep peaks in childhood and declines as we age. Children also display more muscle activity or twitching when the body is paralyzed during sleep.

Together with the misfiring of paralysis in sleep disorders and cognitive decline, it’s possible that this twitching guides the brain in “wiring or rewiring or learning to rewire itself,” Peever explains.

Meanwhile, he says, better understanding of the link between sleep disorders and neurodegeneration provides clinicians with a critical “window of opportunity” for developing and testing treatments for diseases such as Parkinson’s. “It’s an early warning sign.”

Boosting brain recovery

Brain injury provides another window into the link between sleep and cognitive recovery and decline.

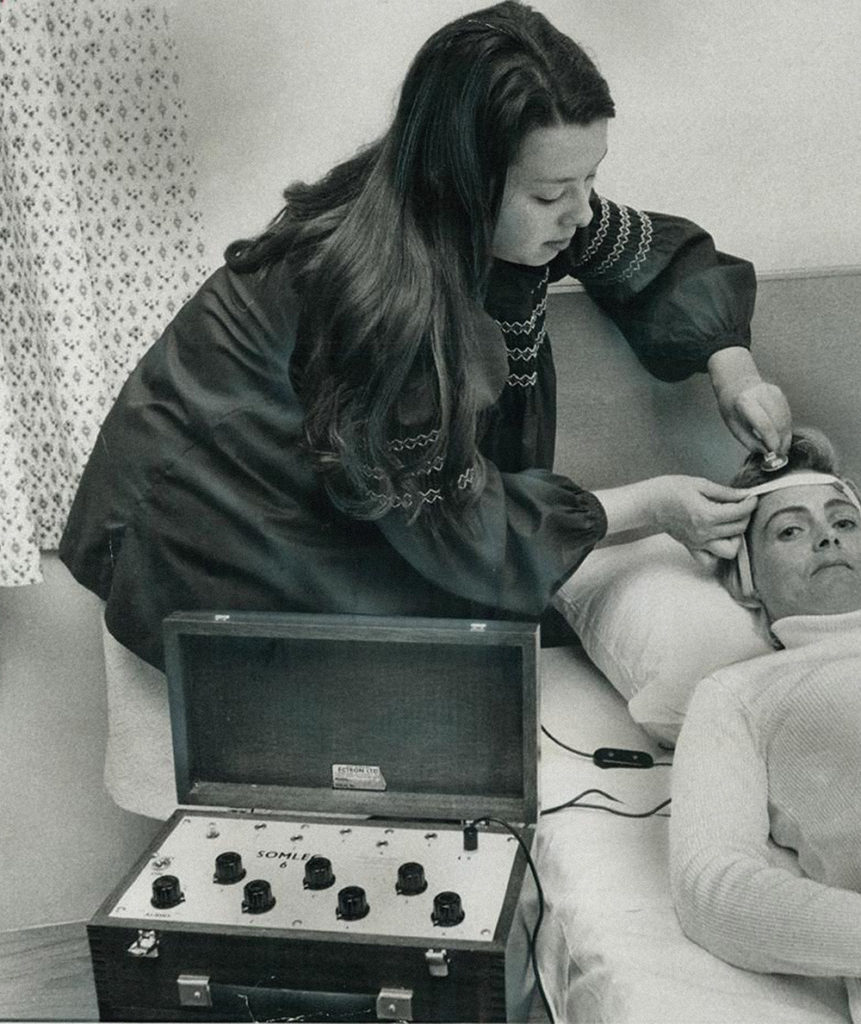

Physician Tatyana Mollayeva (PhD ’15) was working at a sleep clinic as well as in the insurance sector handling disability claims when she noticed an overlap in her clients with sleep disorders and those with ongoing disability from traumatic brain injury (TBI). Intrigued, Mollayeva investigated the apparent connection for her PhD research at Temerty Medicine’s Rehabilitation Sciences Institute (RSI). She found that nearly 70 per cent of patients with delayed recovery from mild TBI also reported clinical insomnia, and those with more severe insomnia experienced higher levels of disability.

Later studies have reaffirmed this link, with sleep

disorders estimated to occur in roughly half of patients with a TBI.

Now an assistant professor at RSI and U of T’s

Dalla Lana School of Public Health, and a scientist at University Health Network’s KITE Research Institute, Mollayeva continues to study the connection between brain health and sleep health. In a study of more than 700,000 Ontarians with TBI, she found that those who also had a sleep disorder when they were diagnosed with TBI were 25 per cent more likely to develop dementia over four years.

Increasingly, research is suggesting that these findings may reflect an inflammatory feedback loop, in which injury triggers brain inflammation that disrupts sleep, which in turn exacerbates inflammation, increasing the risk for a delayed recovery and cognitive decline.

A similar inflammatory feedback loop may be at play in other conditions commonly linked with sleep disruptions, such as depression.

Sleep and mental health

Indeed, sleep disorders are often overlooked because they accompany or mimic the symptoms of other conditions, especially mental disorders.

The criteria for depression, for example, includes sleeping significantly less or more than usual, says Jennifer Hirsch (PGME ’13), a psychiatrist and sleep medicine specialist, as well as a lecturer at Temerty Medicine. Meanwhile, sleep disturbances are associated with almost all anxiety disorders, as well as bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.

“That’s why it’s so important to take a detailed history,” Hirsch says. “Because you’re trying to understand — is this plain insomnia, or is this masking another sleep disorder like restless legs, or is this actually a symptom of a psychiatric illness?”

Parsing sleep disorders from psychiatric conditions and treating them in concert is crucial because one can exacerbate the other.

“If you have a patient with depression and they’re in remission but they have insomnia, that’s the biggest risk factor for their depression coming back,” Hirsch says.

She also says that sleep plays an important role in bipolar disorder: “The odds of relapsing into another manic episode are so high that making sure your patient is sleeping, no matter what combination of sleep pills it takes, is important.”

And for new mothers, who are vulnerable to sleep disorders and mental health exacerbations, Hirsch says, “There’s no medication in the world that’s going to be as helpful for depression or anxiety as getting sleep.”

Watching the clock

Along with the increased awareness of and interest in improving sleep come new anxieties about getting enough sleep.

“I get very interesting referrals now of people who are probably sleeping just fine but want to optimize,” Hirsch says. “There’s this sort of obsessiveness, like, ‘Am I getting enough deep sleep? I’m getting seven or eight hours, but is it a good seven or eight?’”

“Insomnia involves this sort of obsession too,” Hirsch continues. “We lie in bed wishing we were sleeping and thinking about how bad we’re going to feel if we don’t or that we’re going to get dementia.” However, too much focus on sleep only reinforces trouble falling asleep, she says.

Sleep needs are likely more individual than many realize. “In my clinical experience, for everyone who feels pretty good at five to six hours, there’s someone who really does need nine to ten,” Hirsch says. When extremes of too much or too little sleep impact daily functioning, “that’s when we need to intervene.”

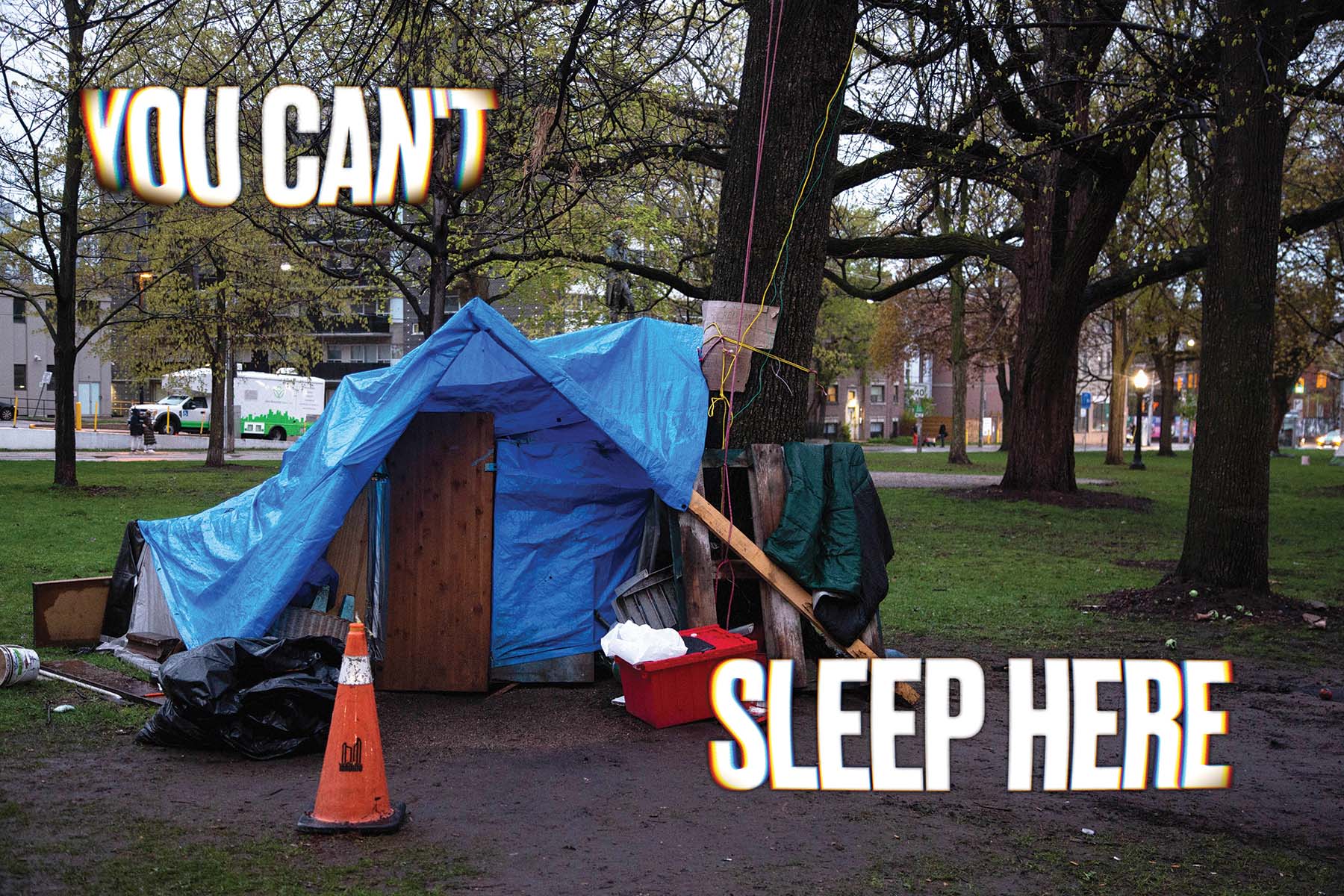

For those raising young children or living in less-than-ideal environments, “your sleep can’t be as perfect as the textbook tells you,” Hirsch says. “I don’t feel there are enough caveats in sleep recommendations.”

Quality over quantity

According to Peever, who helped draft international sleep guidelines, “the science is very clear that if you’re below six hours per night as an adult there are a host of issues that come along with that.”

Meanwhile, longer than recommended sleep duration in seniors has been linked with worse sleep quality, poorer general health and a higher risk of death.

But quantity of sleep isn’t the only measure to keep in mind. “You really have to view sleep as a continuum, and it’s the entire cycle that seems to be important,” Peever says. “So probably the quality of sleep is more important than the actual quantity.”

With new devices such as smart watches collecting sleep data over long periods of time, Murray expects to see a more nuanced picture of sleep emerge based on “weekly, monthly, seasonal and lifetime behaviours.”

“If we tap this data properly, we’re going to have huge insights,” he says. For example, “people who have a very short REM latency — the time from when they fall asleep to when they go into REM — are more prone to depression. That’s an objective marker you can track that’s not influenced by over- or under-reporting.

“If you were going to assess how a drug worked, that could be a way to measure it and, in fact, we know that effective drugs for depression lengthen the non-REM/REM cycle.”

As researchers use artificial intelligence to extract hidden signals from sleep data, “I think we’ll get a lot deeper,” Murray says. Until then, “if you’re wondering why somebody is unwell and you haven’t got a good explanation, think about sleep.”