What can the face reveal and conceal about pain?

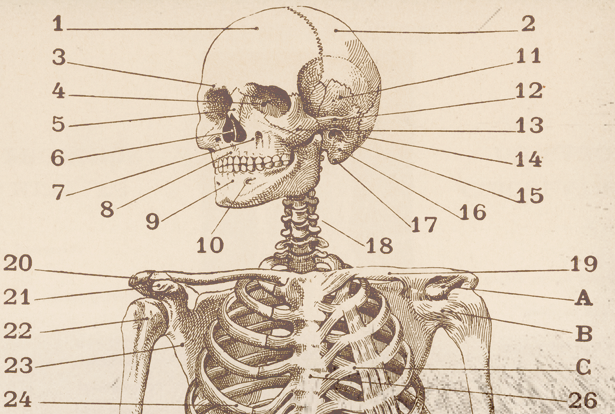

Like lightning to the face. That’s how Professor Mojgan Hodaie (MSc ’94, PGME ’04) says her patients with trigeminal neuralgia describe their pain. Considered one of the most excruciating pain disorders, the condition involves the misfiring of powerful pain signals from the face to the brain.

In one case, a patient was completely debilitated when a single snowflake landed on his cheek during a winter stroll.

“The pain was so severe that he had to hold a lamppost for about 20 minutes before he could keep walking,” says Hodaie, a professor in the Department of Surgery at the Temerty Faculty of Medicine. “Everyday things like speaking, kissing, having a bite to eat — they all become time bombs because patients never know when they’ll be hit by a massive jolt of sharp pain.”

Roughly one in 20,000 people have trigeminal neuralgia. It is notoriously difficult to diagnose, and many people live with extreme pain for decades before receiving treatment. Researchers are exploring what the face can reveal about complex pain conditions.

For Hodaie and her colleagues at Temerty Medicine, that means developing advanced imaging techniques to pull back the curtain on “invisible” pain.

“When patients get surgery for a brain tumour or a broken bone, a surgeon can show you afterwards that the tumour is gone or the bone is fixed,” Hodaie explains. “When patients with trigeminal neuralgia ask if their pain will be gone after surgery, I only have general statistics to give them. In 2021, we owe our patients much more than that.”

The changing face of pain

Until relatively recently, medicine has tended to define and treat pain as a response to physical illness or injury. This narrow view has led to blind spots in care — from overprescribing short-term painkillers for long-term conditions, to undertreating people whose pain doesn’t have an obvious physical cause.

“We’ve been mismanaging chronic pain all these years because, for the most part, we were using acute pain management principles,” says Professor Tania Di Renna (PGME ’03), an assistant professor in Temerty Medicine’s Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine.

Di Renna says there is growing recognition that persistent pain can be understood as a complex interaction between the body, mind and emotions.

“That emotional component has a huge overlay with how people perceive pain,” Di Renna says. Emerging neuroscience and psychological evidence show substantial similarities between physical and social pain, including shared inflammatory responses and neural pathways.

People in prolonged physical pain are more likely to develop mental disorders such as depression and anxiety, and emotional trauma in childhood increases the likelihood of developing chronic pain as an adult. Indeed, just looking at pained facial expressions can increase the perception of pain, while faking a smile can decrease it. This new understanding of pain requires an interdisciplinary approach to treatment, Di Renna says.

As the medical director of the Toronto Academic Pain Medicine Institute (TAPMI), Di Renna oversees a program in which doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, psychologists and other experts work together to support patients to “live a full life despite having pain.” In addition to medication, she says, “You need movement, you need physiotherapy, and you need psychological therapies.”

According to Professor Yasmine Hoydonckx (MSc ’21), a craniofacial pain specialist at TAPMI and an assistant professor in Temerty Medicine’s Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, different disciplines have a lot to learn from each other, especially when diagnosing complex pain. “It’s almost like a puzzle. If you’re lucky, the patient will give you five pieces, and by asking the right questions, you might get another 10 or 15 pieces to find the right diagnosis,” she says. “Together we know much more than apart.”

Solving the mysteries

For people who have trigeminal neuralgia, it can be difficult to know which treatment will work best for a specific patient because the condition defies objective measurement.

By processing MRI images to pick out “tiny, tiny details” in the architecture of the trigeminal nerve, Hodaie’s team has identified factors that distinguish patients who may not benefit from the conventional surgical treatment.

“Now, when those patients come to me, the first option for treatment is neuromodulation,” which alters nerve activity by stimulating specific neural circuits, she says.

By combining advanced brain imaging and psychological tests, Hodaie’s team hopes to chart the relationship between these circuits and extreme facial pain. “Neurovascular contact between the nerve and the blood vessel does not fully explain the whole picture,” she says.

Seeing isn’t always believing

Facial expressions can be an important measure of pain, especially in situations in which patients cannot communicate what they’re feeling. But facial expressions may not be universal and are prone to misinterpretation, says Professor Jennifer Bryan (PGME ’12, PGME ’13). “We have stereotypes about what pain looks like — grimacing, crying, moaning,” says Bryan, an assistant professor in Temerty Medicine’s Department of Medicine.

However, the ways that people express pain may differ depending on cultural factors, their past experiences of pain and their prior interactions with health care providers.

“There are a lot of shorthand approaches to pain management and assessment that don’t work well for the patient,” says Bryan, who is also an emergency physician at University Health Network. Most people are not good at reading subtle expressions — a 2011 paper reported accuracy rates of only 35 to 48 per cent.

Racial and gender biases may further complicate the matter.

Recent research shows that white people have difficulty distinguishing emotions on Black people’s faces and tend to perceive them as angrier than people who are white.

Meanwhile, a 2016 paper found that medical trainees who held false beliefs about racial differences — for example, “Black skin is thicker than white” — were more likely to underestimate and undertreat Black patients’ pain.

Chronic pain patients, especially women and people of colour, report feeling pressured to express their pain in specific ways for health care professionals to believe them. And growing concern about opioid abuse has contributed to some doctors automatically distrusting patients’ reports as “drug seeking.”

“It has been a challenge for many people to come to grips with the fact that we have implicit and explicit biases, and we don’t leave those outside of our hospitals or clinics when we’re treating patients,” Bryan says. In the future, artificial intelligence may help cut through some of these biases, she noted.

Professor Babak Taati, a scientist at the University Health Network’s KITE Research Institute, has developed facial recognition technology to detect pain in long-term care residents with dementia. People with dementia often suffer from unrecognized pain for “days, weeks or months at a time,” says Taati, who is also an assistant professor of computer science at the University of Toronto. Although long-term care workers can assess patients’ pain, the frequency of these checks vary depending on staffing and local regulations.

Meanwhile, misunderstanding signs of distress may lead health care workers to prescribe antipsychotics instead of the pain medicines that patients need, Taati says.

“Violence and aggression are common in patients with dementia, and some of that is linked to untreated pain,” he says.

Sickle cell disease — a blood disorder that mainly affects Black people and can cause unpredictable, intense pain — is another perfect storm for misunderstanding.

“Oftentimes, folks with sickle cell have developed coping strategies to calm and distract themselves, like looking at their phones or having something to eat,” Bryan says.

Health care providers can misinterpret these strategies as signs that the person isn’t in pain.

According to one 2020 study, patients with sickle cell often struggle to quantify their pain using clinical scales. Mutual distrust shapes how they communicate with providers, too, further complicating clinical assessments.

“If we think we can understand someone’s pain just by looking at them, we risk underestimating them, undertreating them and really losing their trust,” says Bryan. “The gold standard for assessing pain is simply asking, ‘How much pain are you having right now?’” ▲

What if brain stimulation can change the way you see yourself?

Story by Julie Traves

They describe themselves as ugly, deformed, even monstrous. On average, they spend anywhere from three to eight hours a day on mirror checks and grooming. (Let that sink in.) Some cannot leave the house. They miss school. They lose jobs. Many are suicidal. And yet, as Professor Jamie Feusner explains, “These are people who look like everyone else.”

What they suffer from is body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), a condition that can distort how people see their face as well as their physique.

“People with BDD perceive that they have defects, most often to do with their skin, their hair or their nose. But these perceived defects are just not there, or barely noticeable to anyone else,” says Feusner, a professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the Temerty Faculty of Medicine.

BDD occurs in about one in 40 people — making it more prevalent than schizophrenia. But many people with BDD never get help. They believe they have a physical problem, not a mental health condition. And when they do seek counselling, psychiatrists don’t always recognize the symptoms of BDD.

“It’s really understudied and often missed by health care professionals,” Feusner says.

Where does BDD come from?

It’s hard not to wonder whether social media use might at least be a risk factor for BDD. On the discussion website Reddit, there’s a thread called “Am I Ugly?” Its 232,000 members post selfies, mostly of their face, captured on different days and at different angles and then, well, await judgment.

Writes one 17-year-old boy: “Am I ugly? I have really bad anxiety and I just want some honest opinions as to how good/bad I look to other people.”

A post from a 16-year-old girl reads: “I have been struggle [sic] with depression and I have no concept of what I look like.” A number of users actually name-check “body dysmorphia.” “It’s one hell of a drug,” one teenager exclaims.

The disorder’s onset is generally adolescence, which could explain why there are also BDD videos on TikTok that have generated millions of views. But there’s no evidence (yet) that the prevalence of BDD is increasing among Gen Z. Nor have the last 18 months of Zoom calls led to a surge in cases among adults.

Peggy Richter is an associate professor with Temerty Medicine’s Department of Psychiatry.

She also leads the obsessive compulsive disorders program at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre and runs therapy groups for people with BDD. “I haven’t seen an uptick in BDD during the pandemic,” she says.

If anything, some of her patients find virtual socializing (not to mention masking) a relief. One such patient is a woman in her 30s who feels she’s “repulsive” because, like many people her age, she has some slight skin discoloration. Before the pandemic, she had stopped attending her kids’ school events because she didn’t want to be seen in daylight.

“For her, Zoom is extremely comfortable,” says Richter, “because she can set it up with lower light.”

Culture affects the particulars of BDD; fixations on body shape vary by geography. North American men, for example, are more likely to covet a bulky, muscular frame than their European counterparts, says Feusner. A focus on the hips, buttocks and thighs is more common among women in South America than in North America, he adds. But the chief preoccupation for people with BDD is their face or head.

One paper indicates that more than 70 per cent of people focus on their skin, more than 50 per cent are concerned with their hair, and about one-third are preoccupied with their noses. Some aspects of what makes one face more beautiful than another are universal, says Feusner.

“Smooth skin and facial symmetry are perceived as attractive by all humans,” he says. “Even infants will look longer at images that are symmetric.”

Richter describes a patient who, after a blow to his nose, became plagued by the belief that it looked “very off and asymmetric. He would take photographs of himself multiple times a day to see what he looked like to others, and he was constantly checking his nose and touching it,” she says. That a vast majority of people with BDD — between 71 and 76 per cent — seek plastic surgery to fix such “defects” is hardly surprising.

Identifying unrealistic expectations

Professor Jamil Ahmad (BSc ’99, PGME ’10) is the director of research and education at The Plastic Surgery Clinic in Mississauga, Ontario. He says he can “count on one hand” the number of patients he’s seen in 11 years of practice who “clearly have BDD.”

Rhinoplasty is their most common request. But they usually present with concerns about what Ahmad says are perfectly fine noses. “There’s literally nothing I could do to improve them,” he says, adding that he’s declined patient requests to operate in these cases.

Cosmetic surgeons who do proceed with surgery on patients with BDD soon find that the patients are “profoundly unhappy” with any results, he says.

“I don’t think any reputable or self-respecting plastic surgeon wants to operate on a patient they know they can never make happy,” says Ahmad, an assistant professor in Temerty Medicine’s Department of Surgery. “It’s a hopeless situation.”

Richter’s patient never sought a nose job. But in his 30s, he was offered a Botox injection to reduce the creases in his forehead. Instead of making him feel better about his face, it simply shifted his focus from his nose to his forehead. Now he compulsively checks and photographs his forehead, and wears hats to camouflage his appearance. Richter says that treatment can help relieve the pain that people with BDD experience — shame, self-loathing, anxiety and depression. A number of studies have shown that serotonin reuptake inhibitors reduce the intensity and frequency of worries about appearance.

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) helps people with BDD identify “maladaptive thoughts” such as all-or-nothing thinking, mind-reading and personalization. It also reduces compulsive behaviours, such as mirror-checking, which make the disorder worse. As Richter points out, though, “Many patients with BDD have limited insight into their illness.” Some are convinced they have defects one day but not the next.

The role of the brain

New research conducted by Feusner and six other scientists may offer further understanding of what causes such profound distortions of perception in people with BDD. Feusner’s work focuses on visual processing systems in the brain.

To make sense of the images we see, there are two different streams that start in the visual cortex, he explains. One is the dorsal pathway, which leads to the parietal lobe; the other is the ventral pathway, which leads to the temporal lobe.

The dorsal stream acts as a sort of template for visual information, allowing us to quickly process the global or holistic aspects of what we see, as well as their relationship to one another, says Feusner, “OK, oval shape — it’s a face. Eyes are above the nose …”

In parallel, the ventral stream fills in the details: These are lines. Those are pores. That’s hair. This is an eyelash.

A number of studies suggest that in people with BDD, both visual systems in the brain may not be working at equal capacity. The brains of people with BDD may do an all right job of processing details, using the ventral pathway. But the dorsal stream may be less successful in grasping the bigger picture. In other words, their fixation on specific aspects of their face and body may be a perceptual, not just psychological, problem.

To learn more, a recent pilot study by Feusner used repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS). This non-invasive technique applies magnetic fields to the scalp to carry electrical currents to the brain. In this case, the researchers induced currents on the scalps of 14 people with BDD. The area targeted by researchers was in the dorsal visual pathways of the participants’ brains. Half received full intensity “bursts.” The other half were given low-intensity “sham” stimulation.

Shortly after rTMS, researchers measured how satisfied participants felt with their appearance. Those who received full bursts experienced “a significant improvement in body image,” says Feusner. This adds weight to conjectures that BDD may be a problem of global (dorsal) visual processing and suggests that rTMS treatments may help. As Feusner is quick to point out, though, the experiment was only a pilot study.

BDD occurs in about one in 40 people — making it more prevalent than schizophrenia

A vicious circle?

Feusner says it’s also possible that the behaviour of people with BDD may actually alter their brains. They might become self-conscious, start scrutinizing their faces, then, as this focus is repeated again and again and again, develop a stronger capacity to process detail and weaken global processing in the dorsal stream.

Ultimately, says Feusner, “What someone is seeing in the mirror may not be ‘reality’ — we don’t know the objective reality about the way we look, and there really isn’t one.”

Most of us are not bothered by this, beyond the occasional dissatisfaction with photos of ourselves taken at unusual angles, say, or what we believe is not our best side. But for people with BDD, the gap between how they see themselves and what’s really there is less like a crack and more like a horrifying chasm.

Up to 60 per cent of people with BDD have beliefs about their appearance that reach delusional levels. About 25 per cent of people with the disorder try to take their own lives.

Says Feusner, “There are no clear solutions yet, but if we can understand the brain well enough, we may be able to develop treatments that will remediate abnormalities.”

There is certainly an unmet need for additional treatment options, says Richter. BDD is incurable.

“While CBT can be very helpful, there are many people with BDD who are not prepared or willing for the challenges CBT presents,” she says. “The majority will continue to suffer.” ▲