What do we all have in common?

Birth is where it starts.

The highs and lows of the human experience originate from one place. Creation.

Welcome to the beginning.

Again.

What do we all have in common?

Birth is where it starts.

The highs and lows of the human experience originate from one place. Creation.

Welcome to the beginning.

Again.

Illustration by Sid Sharp

By Erin Howe

Parenthood bore no resemblance to what Sumedha Arya (MD ’17) saw while scrolling though Instagram and feeding her three-month-old daughter at 3 a.m. this spring. “There were pictures of glamourous women nursing their babies or wearing full makeup and a pumping bra. They made motherhood look easy but here I was, with spit-up on my shoulder, leaking milk, tears and blood while watching reruns of ‘The Office,’” she recalls.

After welcoming her first child in December 2021, the fifth-year Temerty Faculty of Medicine hematology resident struggled to establish her milk supply. Arya tried medication. Then she began triple-feeding — a gruelling, round-the-clock schedule of breastfeeding, pumping and then feeding her newborn the fresh milk. None of it was easy. And no part of it felt intuitive.

Nor did her experience live up to any of the stereotypical ideals — that pregnancy, birth and new motherhood should be beautiful, natural and even ethereal. The phenomenon is sometimes called the goddess myth, an impossible standard that defies, now more than ever, the reality of this key period in people’s lives. And this mythology hurts parents and their children.

The weight of these expectations can begin even before there’s a positive pregnancy test, says Professor Tali Bogler (PGME ’13, ’15). When people are trying to conceive, there’s pressure. And if people require fertility treatments or can’t conceive immediately, there can be a sense of failure, she says. When she was pregnant, Bogler, an assistant professor in Temerty Medicine’s Department of Family and Community Medicine and the mother of four-year old twins, fielded numerous questions about whether her pregnancy was “natural.” “What does that even mean, anyway? Who gets to define what natural is?,” wonders Bogler, who is also chair of Family Medicine Obstetrics at Unity Health Toronto’s St. Michael’s Hospital.

The list of decisions parents feel they will be judged on is lengthy — from giving birth vaginally or by caesarean section, to having an epidural or not, to breastfeeding or formula feeding. And expectant parents bear these expectations during an already sensitive period when hormones and emotions are running high, and sleep is running low. Stigma can interfere with soon-to-be parents getting the help they need, says Bogler.

Despite well-established evidence that antidepressants are safe to use in pregnancy, many expectant parents still worry that taking them could harm their baby. “There can be this feeling in pregnancy that, ‘I am the vessel carrying the fetus and must do everything possible to protect it, and those concerns can mean questions about medications, vaccines, or anything else,” says Bogler. “And that eliminates the autonomy of the individual, the pregnant person, and their own health priorities.”

COVID-19 also had a bombshell effect on new parents — with wider-ranging health effects that are yet to be seen.

Like many expectant parents, public health precautions required Arya to attend her prenatal appointments alone. In the past, birth has always been a family event, says Modupe Tunde-Byass (PGME ’04), an assistant professor in Temerty Medicine’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. To bridge the gap created by COVID-related measures, Professor Tunde-Byass invited her patients to include their partners in the appointments by using video chat or speaker phone so they could be part of what was happening and ask any questions they had. “It can be lonely or sad for these parents,” says Tunde-Byass, who practises at North York General Hospital. “People who already have children know what they’re missing. And first-time parents said to me, ‘I wish my partner could see.’”

Even before the pandemic, Canadian research showed that nearly one-quarter of mothers experienced postpartum depression and anxiety. No wonder so many seemed to feel more defeated than deified.

Between March and November of 2020, research published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal showed that during the first nine months of the pandemic, the number of new mothers visiting their doctor to discuss concerns about their mental health swelled by about 30 per cent. A study in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology Maternal-Fetal Medicine that new mothers were more than twice as likely to have postnatal depression during the pandemic than before it.

Study author and Temerty Medicine Professor Stephen Matthews points out that perinatal mood and anxiety disorders are strongly linked to adverse birth outcomes. Preterm birth, parents finding it hard to bond with their baby, and delayed infant cognitive and emotional development are among the risks of untreated depression and anxiety.

“A baby gestates in one person’s body, but the mother is part of a broader context and how they cope is related to how the whole unit is coping,” says Matthews, a professor in the Departments of Physiology, Obstetrics and Gynaecology, and Medicine. “The person who is pregnant is not responsible for the broader context.”

Much of Matthews’ research focuses on the role of stress hormones in fetal brain development and how molecular processes can impact brain development long term. More recently, he’s begun to explore the role of fathers in making a healthy baby. Though there’s little human evidence so far, Matthews says animal studies show differences in the sperm of fathers with obesity or type 2 diabetes compared to fathers without the conditions. The differences are associated with a greater risk of cardio-metabolic problems among the offspring. Scientists have also observed differences in the microRNA of sperm in mice who experienced stress. This can alter brain development and stress responses in their offspring. Matthews believes similar effects likely play out in people.

“Thinking only about the maternal environment is an issue because that implies that the mother’s behaviour is all that matters, and that’s just not the case,” says Matthews, who has a lab at Sinai Health’s Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute.

People are often quick to blame themselves when things don’t go as expected

Adding to the complexity of the parenting process is the fact that people are often quick to blame themselves when things don’t go as expected, says Emily Ho (BSc OT ’97, PhD ’19), an assistant professor in Temerty Medicine’s Department of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy.

“Often, when I meet parents of children with congenital limb differences for the first time, I’ll look them in the eye and tell them, ‘This isn’t because of anything you did.’ Do you know how that can relieve a parent?,” asks Professor Ho, who is also an occupational therapist working with children and youth with congenital limb differences at The Hospital for Sick Children. “Sometimes, this is the first time that parents have these feelings acknowledged. I see their eyes well up,” she says.

Parents can struggle to balance their instinct to shelter their children from all harm against knowing how much their kids are capable of, says Ho. “One mother I spoke to told me that she knows there’s this guilt inside her through every decision, whether it’s about a medical procedure or whether to allow her child to do a high-level sport,” says Ho. “The mother tells her child that she is capable of doing anything. But at the same time, this mom just wants to protect her child because, on an emotional level, she feels she couldn’t protect her child before.”

Prospective parents and new parents must also address constantly evolving social expectations around what is right for them and their child, says Milena Forte (PGME ’01), an assistant professor in Temerty Medicine’s Department of Family and Community Medicine and departmental lead for maternity care. “When people talk about natural birth, I always ask my patients, ‘What does natural mean to you?’ People have unrealistic expectations about what birth will entail. Within the medical community, we know some birth plans are completely misleading in that they give people a false sense of control. Plans can change when people enter the labour ward,” she says. Plus, standards about what community looks like after birth have changed, she says.

Professor Forte has noticed a shift in the way families spend the “golden hour” — the 60 minutes after birth finishes. “In the past, someone would go out to the waiting room and tell the loved ones sitting there about their happy news. Now, in addition to focusing on the new baby, parents also use some of that time to share with their smartphones,” says Forte, who is also a family physician at Mount Sinai Hospital. “There can be some added pressure for people to ‘get themselves together’ for that first photo.”

As well, the pregnancy advice Forte says was “heretical” 40 years ago is now much more mainstream. “Look at exercise during pregnancy — which was once discouraged. In the 1980s, we asked, ‘Is this safe?’ Now, we know it has all kinds of beneficial aspects, like decreasing the risk of hypertension, pre-eclampsia and depression,” says Forte.

“Things like skin-to-skin contact after birth, or exposure to vaginal secretions used to be seen as ‘out there.’ Now, science is catching up.” With the bleary-eyed days of early motherhood behind her, Arya says things are going more smoothly now. She’s breastfeeding her daughter, and she supplements with formula. Arya doesn’t regret her decision to use formula when necessary, which she says improved her own well-being. She also takes solace in commiserating with some of her friends, who are also new parents.

“Shared vulnerability is a powerful balm,” says Arya. “As soon as one person opens up, it dampens the isolation and helps make clear that the myths surrounding motherhood are just myths, not reality.” ●

Advertisement

Illustration By Jud Haynes

By John Lorinc

Two questions have intrigued both scientists and philosophers for centuries: What does it mean to be born? And, can we create life outside the womb?

Mike Seed (PGME ’11), an associate professor in Temerty Faculty of Medicine’s Departments of Paediatrics, Medical Imaging, and Obstetrics and Gynaecology, can pinpoint the moment when his team’s work — exploring the possibility of creating artificial placentas for premature babies — served up an aha moment.

Professor Seed, The Hospital for Sick Children’s head of cardiology, is working with a Toronto-based group who want to extend the ground-breaking 2017 work of a research team at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

The U.S. group developed a “biobag” for gestating sheep fetuses, using artificial amniotic fluid, an oxygenator and surgical techniques for swapping out the ewe’s placenta with a “circuit” of tubes designed to siphon in nutrients and gases, and draw out wastes. In effect, they created an artificial placenta.

The Toronto project, which involves graduate

students, is supported by the SickKids Foundation and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. SickKids doesn’t have facilities for pregnant sheep, so Seed opted to work with mini-pig fetuses, which are closer in size to the extremely preterm humans that are the research target. The first 10 experiments failed: The pig fetuses died almost immediately.

Seed’s co-investigator, Christoph Haller (PGME ’17), an assistant professor in Temerty Medicine’s Department of Surgery and a surgeon-investigator at SickKids, knows how challenging it is to insert tubes carrying oxygen and nutrients into the umbilical cord. But the team succeeded in developing an approach to connect the fetus to the oxygenator circuit.

“At one point during one of our recent experiments, the heart rate came down and the blood flow around the circuit was normal,” says Seed. Yet he notes a qualifier: that pig fetus that succeeded had been slightly larger than the others. “That might have been what made the difference,” he allows. “Still, the most important moment for us was when we first managed to get an animal onto the system.”

Earlier this year, the SickKids team embarked on a new set of experiments. While Seed acknowledges there’s likely a long way to go before artificial womb technology can be used to gestate premature human babies, he and others in the field know what they’d like to achieve. They’d like to find a way to prevent the high risk of disability and death that imperils babies born very prematurely, around the threshold of viability, at about 22 or 23 weeks gestation.

These infants spend their first months in an incubator and run a high risk of respiratory, cardiac or cerebral injury. “The existing approach is pretty bad,” Seed says. With advances in fetal surgery, he adds that artificial placentas could enable procedures like cardiac surgery to be carried out more safely. “The artificial placenta could become a vehicle for delivering new experimental treatments such as gene therapy or stem cell therapy,” he says.

Developing mechanical and surgical techniques is only part of the discovery process. Cynthia Maxwell (PGME ’04) is a professor in Temerty Medicine’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology who is participating in Seed’s project. She says the viability of artificial wombs poses critical questions about how health care practitioners work with pregnant people. Professor Maxwell, who is also a maternal fetal medicine specialist at Sinai Health and Women’s College Hospital, says advances in artificial womb techniques will require the development of “fetal ICUs” equipped and staffed to provide specialized care for fetuses. As Maxwell observes, developing this technology poses a fundamental question if there’s an option besides vaginal birth and C-sections. She asks, “What does it mean to be born?”

Bioethicists stress this research is raising important questions about whether the existence of artificial wombs will alter assumptions about pregnancy, uterine transplantation, surrogacy and even the rights of women to obtain an abortion. “In the short term, it may seem like this is about private decisions to be made by individual women with respect to their pregnancy and fetus,” says Françoise Baylis, a professor at Dalhousie University. “But it has broad societal implications, and that’s why it’s really important to involve non-scientists including bioethicists in frontier science.”

Elizabeth Chloe Romanis, an assistant professor in biolaw at Durham University in England, says it will be critical for researchers and university ethics boards around the world to recognize that such technology must not be seen as only an innovative form of clinical treatment if it’s tested on humans. “It will ultimately be an experiment when it’s first used,” she says.

Attempts to build an artificial womb go back to Sweden in the 1950s, and researchers have been picking away at the idea ever since. Artificial wombs, says Seed, “make total sense.”

Premature babies have underdeveloped lungs that are easily damaged. For a fetus, the placenta provides nutrients and hormones, as well as a continuous exchange of gases. “Placentas are unique in terms of that relationship,” says Maxwell.

The oxygenators used in neonatal cardiac surgery have become more sophisticated and similar in their performance to a real placenta, resulting in increasingly convincing artificial placenta experiments in animal models. (Research teams, including those in Michigan and Australia, are also working on artificial placentas.) Seed and Haller’s group discovered that the commercial neonatal oxygenators caused heart failure in their small pig fetuses so decided to add a pump to the circuit.

In a second series of experiments incorporating a pump, the fetuses were much more stable, with the animals surviving for up to a week. Yet the group is still seeing problems with heart failure in their animal subjects and is continuing to modify the circuit in an attempt to more faithfully reproduce the physiology of a real placenta.

Maxwell is focusing on post-procedural issues, such as what will be required in the fetal ICU, environmental issues such as temperature and lighting, and even techniques for mimicking the pregnant person’s movements. “The animal models are super promising,” she says. “The sheep model suggests that you can bring a baby lamb all the way to term, so I think it’s really a matter of time before that technology will be worked out in other animal models, and then we’re able to actually use that for human beings.”

The SickKids team doesn’t anticipate that the artificial placenta will alter the current threshold of fetal viability. “There are likely to be physical constraints in terms of vessel size and blood pressure that mean this approach will primarily be used in extremely preterm babies that currently receive conventional neonatal intensive care,” says Seed. “It’s going to be risky to support a baby on an artificial placenta, such that it will always be much safer for them to remain in utero whenever possible.”

The research has raised important ethical questions about the role of this kind of technology in human reproduction. Romanis’ doctoral studies included several months working with Bernard Dickens, a University of Toronto Faculty of Law professor emeritus. Romanis predicts that it will be ethically challenging to organize clinical trials or obtain informed consent for participation in a clinical trial because pregnant people facing the risk of premature birth still have the option of neonatal intensive care, which is a well-established approach. “I think human trials are going to be really, really complicated,” she says.

Baylis cautions that such research tends to focus on solutions and benefits and neglect potential harms and misuses, such as whether the artificial womb technology could someday be used as an alternative to any pregnancy, and thus serve as a procedure that anti-abortion politicians might mandate as an alternative to ending a pregnancy.

Maxwell notes that the use of artificial womb technology could also pose questions about resource allocation in hospitals, and whether fetal ICUs may come at the expense of other services. But for now, that question may be a way off. “I don’t think we’re at that stage yet,” she says. ●

Photography by Mark Bennett

It’s a test that promises to give a once-over to an embryo before it even gets a shot at becoming a baby, by counting its chromosomes.

But, does it work?

That’s still a matter of debate.

By Alison Motluk

This chromosome-counting technology is called “preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy” or more commonly, PGT-A. The idea is that an embryo with the correct number of chromosomes is more likely to be healthy and therefore, less likely to be miscarried. And that should speed up the time it takes to become a parent.

The U.K.’s fertility regulator, the Human Fertilisation & Embryology Authority, gives PGT-A a red light, saying there is “no evidence” from randomized controlled trials that it improves a patient’s chance of having a baby. A study last year in the New England Journal of Medicine concluded that in women with a good prognosis, regular old in vitro fertilization (IVF) worked just as well without PGT-A. A few U.S. fertility doctors have gone even further, declaring the technology a “dead end” and calling for it to be restricted to research.

Yet PGT-A is offered far and wide, and many fertility doctors consider it useful. Some even call it “revolutionary” and believe that all patients should have the option of using it. PGT-A involves making a small hole in the outer shell of a five- to seven-day-old embryo, which has reached the blastocyst stage, then using a tiny pipette to suction out a half dozen or so cells.

These cells, plucked from the trophectoderm — the part of the embryo that will go on to form the placenta, not the baby itself — are sent to a specialized lab for testing. In the meantime, the embryo is quick-frozen and stored until the results come back a few weeks later.

A healthy person has 46 chromosomes. If all of the biopsied cells have the correct complement, the embryo is deemed euploid, or good. But if all of them have, say, three copies of chromosome 18, which means the baby could die before or shortly after birth, it will be deemed aneuploid, or not good. Sometimes there’s a mix of good and bad, which is called “mosaic,” and other times, though rarely, the results are simply “inconclusive.”

The process isn’t cheap. It can cost anywhere from $3,000 to $8,000 per cycle, say experts. Despite the controversy and cost, PGT-A is becoming increasingly popular in Canada. According to the Canadian Assisted Reproductive Technology Register, 3,974 IVF cycles used PGT-A in 2020, up from just 160 in 2013. That means 26.1 per cent of all IVF cycles used PGT-A in 2020 compared with just 1 per cent seven years earlier. But doctors remain divided.

“PGT-A is one of the real revolutions in reproductive medicine,” says Crystal Chan (MD ’07, MSc ’12, PGME ’13, ’15), an assistant professor in the Temerty Faculty of Medicine’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology.

The first big revolution, says Professor Chan, was being able to make embryos outside of the body, be it through IVF, in which sperm and egg are placed together in a petri dish, or by intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), in which sperm is injected into an egg.

The first outside-the-body conception that led to a live birth occurred in the U.K. in 1978 with the birth of Louise Brown — 44 years ago. The second revolution, says Chan, was being able to vitrify and therefore store excess embryos for future use.

PGT-A, which gives us a way to select which embryos to use, and in which order to use them, is the third big revolution, says Chan, who is also a reproductive endocrinologist and infertility (REI) specialist, and a co-owner and the scientific director of Markham Fertility Centre.

PGT-A is commonly recommended for people who are older, have recurrent implantation failure or unexplained infertility, or who have already given birth to children with chromosomal abnormalities. People wanting to reduce the length of time it takes to get pregnant are also advised to consider it.

Chan, who describes Markham Fertility Centre as a “genetics-forward kind of clinic,” offers PGT-A to all of her patients as an option.

“I always talk about PGT-A when I’m talking about IVF,” says Chan. She points out that everybody makes aneuploid embryos. “It doesn’t matter if you’re 22 years old or 42 years old,” she says. Chan is not alone. Other fertility experts are also in favour of the procedure.

Heather Shapiro (PGME ’92), an associate professor in Temerty Medicine’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, says her patients use PGT-A for a variety of reasons, including avoiding a miscarriage. Miscarriage may not be a big deal for some people, she says, but for others, it can be traumatic.

“There’s a lot of data showing that people abandon treatment more often after miscarriage than after just a failed IVF cycle,” says Professor Shapiro, who is also an REI at Mount Sinai Fertility and Director of the MHSc embryology program at Temerty Medicine.

Enthusiasts notwithstanding, the scientific literature on PGT-A remains equivocal about the benefits. Does the procedure help patients who suffer recurrent pregnancy loss? There is “insufficient evidence.”

Does it help women over age 35 achieve a viable pregnancy more quickly? No randomized controlled trials have tried to answer that question. Most important of all — because this is the only real point of assisted reproduction — does PGT-A improve the chance of going home with a baby? The answer is no.

Despite the controversy and cost, PGT-A is becoming increasingly popular in Canada

Both Chan and Shapiro acknowledge that PGT-A does not increase the likelihood of giving birth to a baby in any given IVF cycle. “It’s not going to make a bad embryo good,” says Chan. But could PGT-A actually make a good embryo bad? That has been a lingering question.

One concern is actual damage to the embryo by taking out a few cells from the trophectoderm. Placental tissue is extremely important for implantation, says Robert Casper, a professor emeritus at Temerty Medicine’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. A trophectoderm biopsy could actually reduce the chance of implantation, says Professor Casper, who is also the Scientific Director at and a founding partner of TRIO Fertility in Toronto.

Another, perhaps larger, worry is that PGT-A might be relegating perfectly good embryos to the trash bin. At issue is whether cells that go on to become the placenta really give an accurate picture of the inner cell mass, which becomes the fetus. (It’s widely agreed that it would not be safe to take cells from the inner cell mass.)

Shapiro is confident that “the biopsy is a pretty good representation of what’s happening in the whole embryo.”

Chan also thinks so, but cautions that PGT-A is not a diagnostic tool but a screening test. “No screening test in all of medicine is completely accurate,” she says.

All patients considering PGT-A at both Markham Fertility Centre and Mount Sinai Fertility see a genetic counsellor to understand the benefits and limitations. Casper is less convinced. He thinks the findings from PGT-A could be misleading. The trophectoderm, he says, can have a variety of cell lines and “doesn’t always reflect what’s actually going on with the baby.”

But if you happen to pick up all abnormal cells, the embryo will be discarded. “My recommendation to my patients, at least right now, is if you have a small number of embryos, three or fewer, you shouldn’t do PGT-A,” says Casper. Because it’s way too risky that you could throw away a normal embryo, and you’ve only got a few to work with.”

Even a mix of good and bad cells can present a problem. Until recently, such mosaic embryos were considered unusable and tossed out. Recently, however, physicians have been cautiously transferring mosaic embryos — and finding that they often develop into what appear to be perfectly healthy babies.

The Canadian Fertility and Andrology Society, an advisory body for fertility care professionals, has published a guideline on PGT-A. (Chan is one of the guideline authors, and Shapiro sits on the clinical practice guideline committee that helped develop it.)

The guideline suggests that in select patients, PGT-A can “improve the likelihood that a transferred embryo will lead to a viable pregnancy,” but concludes that “the current data do not support the universal use of PGT-A for all patients undergoing IVF.”

Karin Hammarberg, a registered nurse and senior research fellow at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, wonders how well people understand the limits of PGT-A and its risks, at least when it comes to how the test is used in Australia. “People pay an awful lot of money for this,” she says.

Hammarberg and colleagues studied how Australian clinics portrayed PGT-A on their websites and found that the benefits tended to be highlighted and the risks minimized.

“I think the gap is in the transparency and the accuracy of information,” she says.

She thinks patients need to carefully consider whether they will really benefit from PGT-A. What are the risks? What are the costs? What are the other options? And what happens if they just forego this sort of testing altogether?

“I think most people are able to make very good decisions for themselves,” says Hammarberg, “as long as they have accurate and really transparent information.” ●

A series of short takes on the question

Illustrations by Elise Conlin

I’ve been working in the maternal mental health field for more than 25 years, providing psychiatric care to people who are pregnant and in the postpartum period.

I help patients manage depression, anxiety and other illnesses. I also assist them with issues like fetal loss, or miscarriage, or fertility problems.

Recently, I met new mothers in Poland who fled from Ukraine after Russia’s invasion. The circumstances they experienced were daunting.

In Ukraine, the biggest issue prospective parents face currently is the stress of the war. Women give birth under bombardment, or in bomb shelters. They are trying to protect their newborns in situations where it’s very difficult to find a safe place. It adds a terrible level of trauma to the birth process.

Mental distress greatly affects pregnant people. It also has an impact on the infants once they are born.

For example, maternal mental health has a strong influence on fetal and infant neurodevelopment. Stress can cause epigenetic changes that may predispose children to future medical and psychiatric disorders.

It’s important to emphasize maternal mental well-being to clinicians. That way, health care providers can recognize when a woman is struggling or in distress, and they can offer appropriate care and support.

Myroslava Romach (MSc ’79, MD ’84, PGME ’89) is a professor in the Temerty Faculty of Medicine’s Departments of Psychiatry and Surgery, and co-director of the Hospital for Sick Children’s Ukraine Paediatric Fellowship Program.

There’s an uncomfortable fact that I’ve seen as an anesthesiologist: Pregnant people in remote and rural communities don’t always receive the same level of care as those who give birth in a city. The problem isn’t new — it’s been around for decades.

More than 20 years ago, I was on a holiday with my family in a remote town in British Columbia. When a local mother showed distress during a complicated childbirth, I was rushed in to help on an emergency basis.

Ultimately, after I provided the anesthetic for a surgical delivery, the woman was able to give birth safely, and the baby’s condition stabilized. But the experience has always been a reminder to me about the rural-urban divide in birth care in Canada. The gap still exists.

Over the last 20 years, the country has had an erosion of the rural health care workforce, including fewer medical professionals who can provide anesthesia, surgical and obstetrical care to people giving birth.

Health care providers in rural and remote communities can be faced with low case volumes, but they can also have patients with very severe health issues. We need to make sure that we’re training and supporting health services for all Canadians, not only those who live in urban areas.

By using technology to mentor anesthesia providers in rural and remote communities, we can help support health care providers as well as patients who want to give birth close to their home.

Beverley Orser (PGME ’87, PhD ’95) is a professor and the chair of Temerty Faculty of Medicine’s Department of Anesthesiology & Pain Medicine, and a staff anesthesiologist at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre

The COVID-19 pandemic led to changes in the way people access abortion in Canada.

The rise of virtual care meant health care providers could speak to people by phone or through an online platform and provide a prescription for mifegymiso, two drugs that work together to terminate a pregnancy.

For the first time, people could access a medical abortion without the blood tests and ultrasounds required in the past.

I think the rise of what’s known as low-touch or no-touch abortions is important and a change that should stay.

As part of my fellowship at the University of Toronto, I’ve done work with newly arrived refugees in Canada, as well as marginalized and immigrant communities in Toronto.

Some of my patients come to me for reproductive health care without having formal legal status, and many feel vulnerable seeking advice.

Some might be in an abusive relationship and may need guidance on how to proceed with a pregnancy — or not proceed with it.

Universal access to low- or no-touch medical abortions can make a difference for patients. It can increase their feeling of safety with the process.

It can help people who are limited geographically or have limited funds to access care. Improving low-touch and no-touch abortion care helps people achieve reproductive autonomy.

Jenny Yang is the global women’s health and equity fellow in Temerty Medicine’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, and an obstetrician-gynaecologist from Australia.

There’s a story I’ve heard for decades in my family. I often share it with students when I am educating them about the importance of equity, diversity and inclusion in health care.

It happened after my mother, a Black woman from Jamaica, had given birth to a child at a Toronto hospital. The child was me. This was at a time when people from Africa and the Caribbean made up less than two per cent of the city’s population.

After my birth, my mother wanted to nurse me. She asked the nurse, “Where’s my baby?” The nurse told her that I was nowhere to be found. “There are no Black babies in the nursery,” said the nurse flippantly.

My mom had a choice about how to respond. She reflected on the situation and then changed that moment into a teaching opportunity. “Instead of looking for someone who you think looks like me, go back and look for a human being. She has a name,” my mother told the nurse. “It’s Stephanie.” Shortly after, the nurse brought me to my mother.

I think the experience my mother had is illuminating because it teaches us about allyship. An ally uses their privilege for good. My mother used her privilege of language, experience and education to teach the nurse, even though it was not my mother’s burden to bear.

In the future, I think the birth experience will be much better when we all commit to work in allyship with the families we serve. It takes a community of allies to raise a child, and we need more of them.

Stephanie Lurch (BSc PT ’91) is an assistant professor and the equity, anti-racism and social accountability academic lead at Temerty Medicine’s Department of Physical Therapy.

A central focus of my work is to improve access to human breast milk for vulnerable infants in the hospital. Breast milk boosts neurodevelopment and reduces infections among these babies.

In Toronto, MaxiMOM, which stands for Maximizing Mothers’ Milk for Preterm Infants, does research on human milk.

The Rogers Hixon Ontario Human Milk Bank also collects and pasteurizes donated human milk to give to hospitalized babies when a mother’s milk is unavailable.

Before vulnerable infants receive donor breast milk, it must be pasteurized to remove any pathogens that could be passed onto a child.

An innovation that could greatly help with improving the quality of donor breast milk is improving the process of pasteurization. In particular, my team and I are working to develop non-thermal high-pressure processing of donated milk. Right now, milk banks must rely on 100-year-old technology.

Perfecting this process will help keep more of the bio-active components in human milk in donor milk, including antibodies, lactoferrin and lysozyme, which we know help fight viruses like COVID-19. We need better technologies for this.

Lives count on it.

Deborah O’Connor is a professor and chair of Temerty Faculty of Medicine’s Department of Nutritional Sciences, and a scientist at The Hospital for Sick Children.

I’m fascinated with how we can use technological tools around the world to help train health care providers who assist with childbirth.

I did my undergraduate medical education in Pakistan. Then, I did training at a surgical simulation centre with robotic dummies in Ireland while I was doing a Master’s degree.

During my education, I became interested in ways to provide better surgical care in a global context. It’s startling to think we might be able to stop more than 100,000 maternal deaths if there is better surgical and anesthesia care.

Right now, that care isn’t available to billions of people, including mothers and children. In providing quality care during childbirth, you have to think in terms of trauma-informed care and understand the cultural perspectives of different communities.

My current research is in understanding how quality of care could be improved in Canada. It includes looking at how videos and real-life simulations can teach health care providers different skills, such as how to properly put on

personal protective equipment.

One cool example I recently learned about is the Toronto Video Atlas of Surgery’s pelvic examination module. It’s a fully animated pelvic exam video that teaches health care providers how to communicate with a patient during what can be an invasive, uncomfortable procedure.

I’d love to develop more virtual tools for health care providers around the world. I could see tools that teach how to deliver a baby or how to manage complications during labour. This could be a massive leap for global health care.

Anisa Nazir is a second-year Master’s student at Temerty Medicine’s Institute of Medical Science.

Photography by Mark Bennett

By Maxime Billick

as told to Hilary Caton

I once had a professor tell me: “It’s easy to forget to have children.”

I didn’t really believe her at the time. However, it turns out it wasn’t far from the truth. In the summer of 2021, my 34th birthday was on the horizon. My career accomplishments were well on their way. I was the chief medical resident at Toronto General Hospital. I had invested a significant amount of time and energy in my studies, which included four years of undergraduate education, four years of medical school and four years of residency. I had a clinical fellowship in infectious disease with the University of Toronto that was set to start in July 2022. I had poured my time, energy and focus into my work. The results were clear.

But last August, the words of my professor came back to me, and I started to wonder: Will I be that person who forgets to have children? I began to reflect. I’ve often been labelled a high achiever, career-driven and independent. I was always the woman who didn’t need to rely on anyone, and that’s been very important to me. But I also knew I wanted to have kids one day. The COVID-19 pandemic had staggered my dating life and made me aware of the relatively narrow window of time I had left to have children. So as summer wound down, I acknowledged that my last few years of quality egg production were almost behind me — and that’s when I started to think seriously about freezing my eggs.

People choose to freeze their eggs for a multitude of reasons. Some have health issues, others haven’t found the right partner, and many just aren’t ready to have children yet. For me, freezing my eggs seemed like the best way to relieve some of the anxiety and pressure I felt about having children. To me, it was the ultimate way of taking control of my biological clock. I wanted to achieve my personal goals and have children on my own timeline, not on a timeline prescribed by our patriarchal society, in the way our work and our medical training are arranged. So I said, “Screw the patriarchy. I’m going to do this.” And I did.

Besides, I wasn’t alone — egg freezing is increasingly common for women in high-achieving careers. I know of lawyers, pharmacists and architects who have done it, but the opportunity rings especially true for female physicians. As it so happens, our prime childbearing years inconveniently overlap with our prime training and career-building years.

In a study recently published in JAMA Internal Medicine, researchers learned that female physicians “significantly postponed” pregnancy later than women who are not physicians. The data showed that female physicians typically don’t have their first child until they are 32 years old; for non-physicians, that age is 27. In my case, I was 34 years old and not in a long-term relationship.

My younger self had imagined myself having kids around this age. But my current self knew I wasn’t yet in a place where I could have a child on my own. And, I didn’t want to wait too long to have a child either. I needed a contingency plan. Choosing egg freezing was a tangible way of facing the reality of wanting kids but not finding the right person to have them with. Freezing my eggs just made sense for me from a timing and financial perspective.

The first step in my egg freezing journey was speaking to my family doctor and booking appointments with fertility clinics to learn more about the procedure. Soon after, the entire process was laid out for me. Elective egg freezing, or cryopreservation, usually takes about two or three weeks from starting injections to harvesting the eggs and freezing them. In some cases, it can take a month.

It’s a short length of time; however, it’s a tough process that doesn’t come cheap, unless you happen to work for a company that covers some of the costs. According to a study published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal, the average cost of the procedure is between $9,000 and $17,000 per cycle, with private insurance possibly covering the $3,000 to $8,000 needed for the injections. Then, there is the annual storage fee that costs $300 to $500.

In my case, I was fortunate and privileged to be able to afford the procedure and have the medication covered by insurance. I know many women in this country don’t have this luxury. In January 2022, I made the leap and began the process. I was tasked with injecting four different types of medications and hormones into my body around the same time every day for 10 days. It was relatively painless, and the needles auto-inject the medication like insulin injections do. This part of the process helps stimulate the ovaries to produce multiple eggs at a time. It also involves frequent trips to the fertility clinic for monitoring via ultrasound.

Thankfully, I have a boss who was beyond understanding and encouraging throughout all of this. I was also in my chief resident year, when the majority of my work was administrative or leadership related. This meant more stable working hours, allowing me to discreetly manage the injections and appointments. While the injections were simple and small, the side effects were a different story.

I’m not usually one to veg on the couch, but I would come home from work exhausted, and I had to drag myself off the couch just to roll into bed. I became bloated to the point that it was painful to put on pants, and I had never seen my stomach look as distended as it was. That being said, while uncomfortable, this part of the process was still manageable. It became more challenging after the procedure, when I woke up with terrible cramping for several nights in a row. Physically, that was the hardest part of my journey. Going through the process made me reflect on where I was at in my life.

Not usually one to tweet about personal things, but I think this one’s important: I froze my eggs this week 🥚🥶(!!). It was a relatively straightforward decision, and one I had been thinking about for a while. 1/7🧵

— Maxime Billick (@maximebillick) January 29, 2022

The procedure of retrieving my eggs was similar to that of in vitro fertilization. On January 25, 2022, a doctor used a transvaginal ultrasound probe to locate the mature follicles in my ovaries and then used a suction to retrieve the eggs one by one. Overall, the procedure took about 20 minutes. After the procedure was the hardest part of my journey physically.

For several nights in a row, I woke up with terrible cramping. In retrospect, I think I experienced a mild case of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome, which can happen during this process. Simply put, it’s when the ovaries swell and cause pain due to water retention and the extra hormones in the system. But my eggs were stored in a lab in sub-zero temperatures in downtown Toronto. The eggs now wait for me there, for future use.

I felt liberated. Following a 20-minute surgery, I had successfully secured my fertility freedom. Thanks to the process, I now have the option of having a family later in life through purposeful partnering rather than panic partnering. Or, I might even choose solo parenting. I felt empowered and excited. When I’m ready, I can decide on my own time to have a kid, or two.

A few days after my procedure, I took to Twitter to share my experience because I wanted to empower people who were considering freezing their eggs. I know that in my case, I had unique circumstances. I had the support of my friends, family and colleagues, all of whom thought egg freezing was a great idea.

After I shared details about why I chose to freeze my eggs, I had hundreds of positive responses, including support from complete strangers. My decision seemed to have struck a nerve, in the best possible way. So many different people responded — and not just women contemplating the procedure. Some were curious about what the process entailed. Others shared their stories of success, encouragement or regret over not choosing to freeze their eggs.

If nothing else, I hope sharing my story helps normalize the cryopreservation process. My hope is that knowing about the option encourages people to contemplate their reproductive freedom and realize there isn’t just one path to parenthood.

Maxime Billick is a fourth-year resident at the Temerty Faculty of Medicine, and a graduate of Bowdoin College and McGill University.

Illustration by Ashley Mozo

By Meagan Gillmore

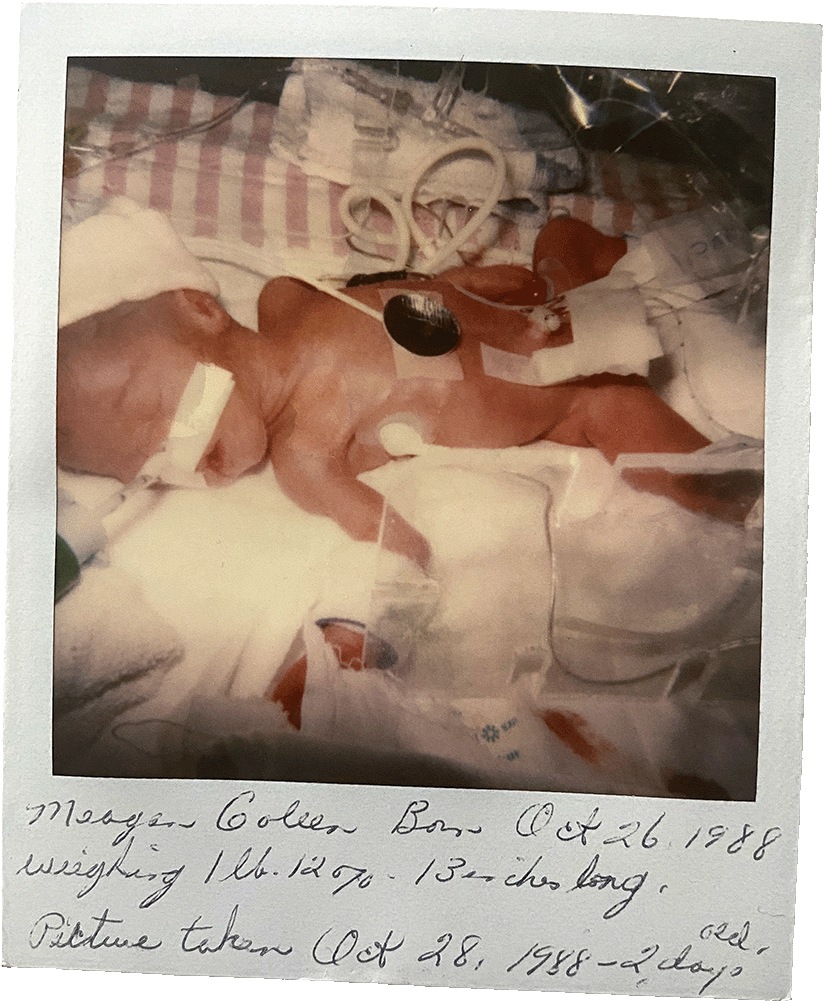

I always debate if I should mention my birth on health forms that ask for my medical history. As I stare, pen raised above the blank line, I ask what would a medical professional learn from reading the words “born prematurely”? How do the first days of my life impact the decades that followed?

I bend close to the health form, steady my good eye as best as I can, and after “medical history” I write, “None.” The medical establishment might beg to differ. In some respects, they’re right. Premature birth, defined by the World Health Organization as any birth before 37 weeks gestation, is an important health concern for children, parents and their broader communities.

Worldwide, premature birth is a leading cause of infant and child disability and death. About eight per cent of births in Canada occur prematurely. At its most basic level, premature birth is a stark reminder that all humans will die. And, despite our efforts to ignore or deny it, we have less control over our lives than we think.

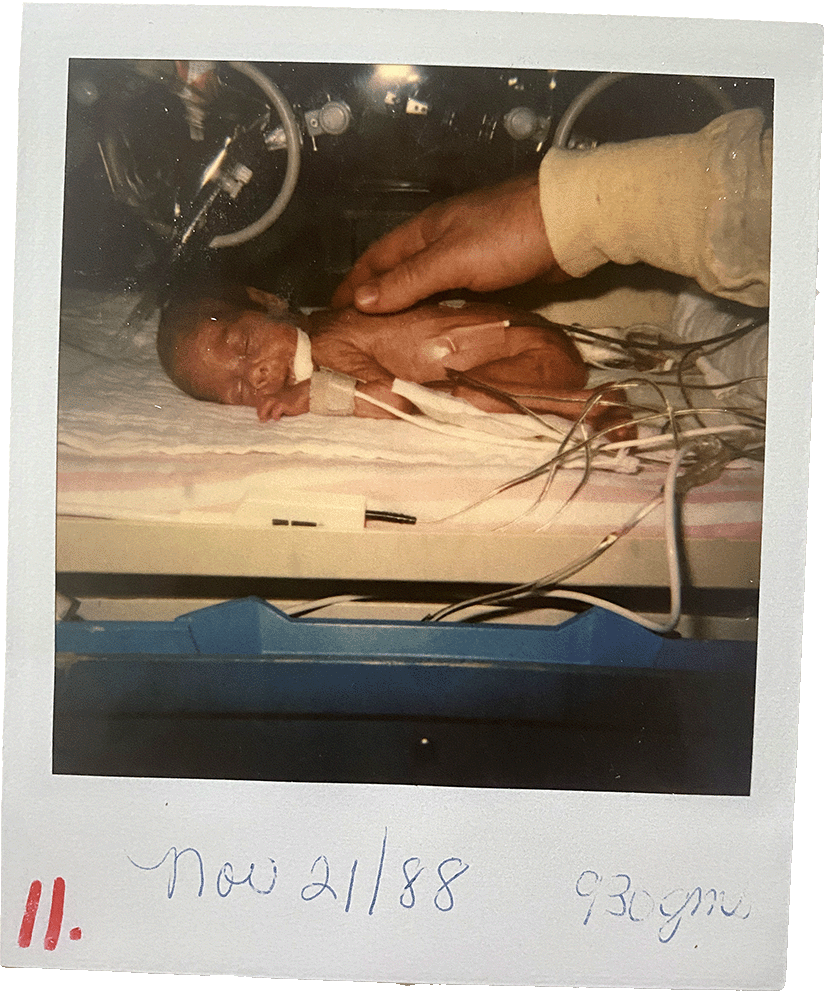

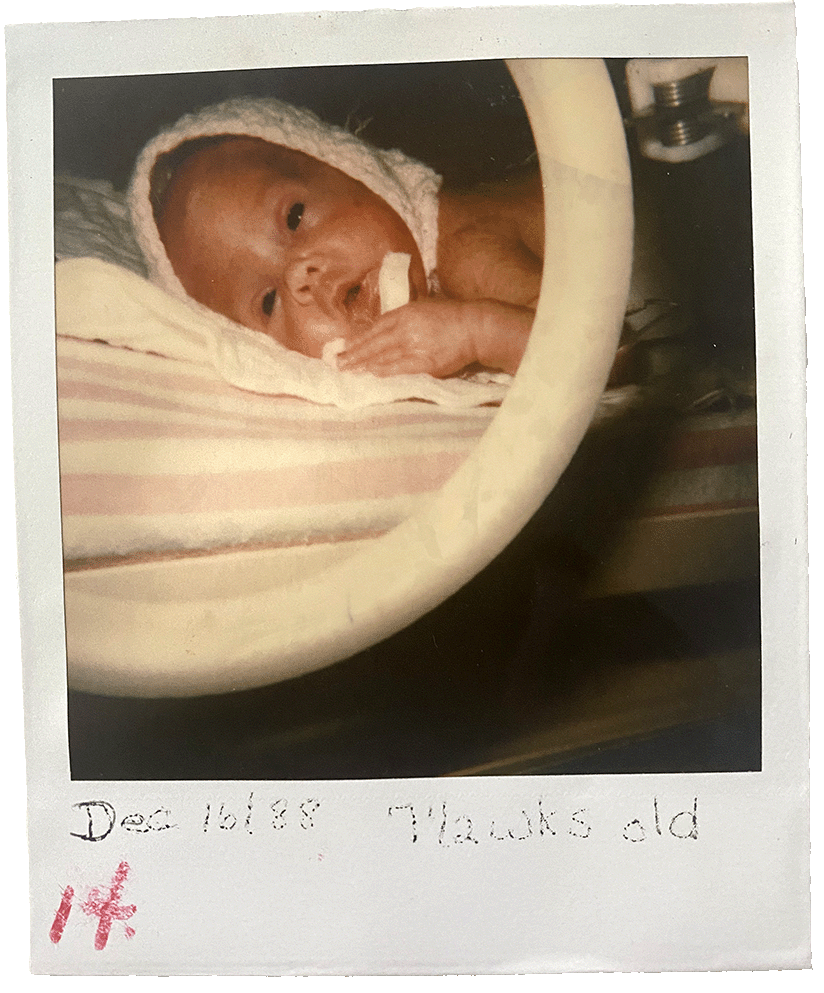

I arrived via emergency caesarian section on October 26, 1988, at 27 weeks. I weighed about 1 pound and 12.5 ounces, or just over 800 grams, lighter than a large bag of candy rockets. I stayed in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) for about three months, until early 1989. My father’s birthday is on January 22 and, as the story goes, I was home for that.

I don’t remember anything about my time in the NICU. I view the girl in the Polaroid photos that the nurses took of me as a stranger. Intellectually, I know she is me and that my personality was forming even as my body and organs finished developing underneath wires and gauze. But I don’t typically consider those months as pivotal in my life.

That is, until I am asked to declare my income. Then, the economic reality of surviving a premature birth becomes clear. Like many premature infants who survive the NICU, I left with a permanent, uncorrectable disability. I have retinopathy of

prematurity, an eye condition I argue begins in the best way possible — with being alive.

I am legally blind. I don’t read braille, but I can’t decipher facial expressions or see street signs. Driving gives me recurring, sweat-inducing nightmares. Adults with disabilities are significantly more likely to struggle finding full-time employment, and I haven’t beaten those odds.

Once, a government-funded ventilator helped me breathe; an incubator was my cradle. Years later, much of my living expenses as a young adult were covered — partially, at least — by a meagre government disability pension. Despite remembering nothing about my first months of life, I’m fascinated by the broader cultural and scientific curiosity surrounding preemies.

Some descriptions of preemies’ lives focus on the NICUs, where alien-looking children with translucent skin spend their first days, weeks or months in a web of tubes, sleeping while monitors whirl and, as is often repeated, defying the odds.

In many cases, these lives are viewed economically: What, inquiring minds ask, does care for these lives cost?

Medically, it’s complicated.

A study — “The economic burden of prematurity in Canada” — found that premature infants collectively have a national cost of $587.1 million in their first 10 years of life, both directly through medical costs or indirectly through the lost productivity of their caregivers. The study further estimates that in their first decade, a child born in Canada before 28 weeks costs $67,467 to care for, including direct medical costs and parental out-of-pocket expenses.

There seems to be an unspoken question lingering in the research: Who is going to carry these costs? In 2020, a study published in Seminars in Fetal & Neonatal Medicine described the physical, economic and social well-being of young adults born prematurely.

Some descriptions fit me. I receive social assistance, although in lower amounts when my employment increases. I’m unmarried and childless. I’ve never had a romantic relationship.

If I do have children, research from U of T’s Lesley A. Tarasoff (PhD ’18) indicates that because I have a sensory disability, my children have a greater chance of being born prematurely or, at least, of having a low birth weight.

Because of the high incidence of disability among premature infants, my potential children may also experience the poverty often associated with having a disability.

However, when older premature children describe their well-being, results aren’t all dispiriting. Some of us hesitate to even assign negative qualities to our disabilities.

My time in a hospital unit doesn’t tell me I’m a burden; it shows me I am loved

One 2022 study reports that, despite struggling to read newspapers or recognize friends from across the street, 19-year-olds with retinopathy of prematurity say they have good visual function.

Research also suggests that extreme prematurity may contribute to a lower income and the lack of romantic relationships — two often difficult aspects of my life. The study, however, warns against describing the lives of premature infants in bleak, economic terms. It notes that “negative effects of extreme prematurity” are limited to a small subgroup. It concludes, “The value of life should not be measured purely in economic terms.”

It makes me sad that this truth needs to be emphasized.

If preemies’ lives are burdens, it’s not because they’re heavy. It’s because current social structures are often not strong

enough to help people impacted by prematurity to fully live their lives. As a child, I was hailed a survivor. But the supports of an NICU don’t continue outside of hospitals. As a young adult, I often felt that my life was reduced to just surviving — and no one cheered for that.

There is a psychological weight that comes with belonging to a group of people whose lives are constantly being monitored and measured. For me, there is a heaviness of being a tiny, early baby; it’s the burden of sharing what I was given in the NICU. Ultimately, my time in a hospital unit doesn’t tell me I’m a burden; it shows me I am loved.

I know I am loved because hundreds of people prayed my mother and me through our time in the hospital, and because families fed my father, brother and sister when my mother and I were in the hospital. I know I’m loved by the outfits my maternal grandmother made, patterned after doll clothes so I’d have something that actually fit.

I know it by the desks my maternal grandfather made for me as a child so I could more easily see my schoolbooks. I know I am precious by the awe and gratitude in my paternal grandfather’s voice as he shared the story about how, after seeing my tiny body in an incubator, a nurse rebuked him for suggesting to my grandmother that I wouldn’t survive.

Years later, my grandmother turned to me in the middle of a relative’s discourse about the cost of premature babies and sternly reminded me that my parents were not in debt because of my infancy. And I know it every time I hold a premature baby and remind them that strength often comes in being held.

At its most basic level, premature birth is a stark reminder that while we have less control over our lives than we like to think we do, we are valued more than we know. ●

By Lauren Vogel

Congenital syphilis, which passes from mother to baby during pregnancy, isn’t something clinicians expect to see in a developed country with universal health care.

But, as syphilis has resurged over the past decade, including among young women, Canada has reported record spikes in the number of babies born with the disease.

Without treatment, babies born with congenital syphilis can suffer terrible health consequences — from bone damage and severe anemia to meningitis and nerve problems that can cause blindness and deafness.

In both 2019 and 2020, more than 50 infants across the country were diagnosed with early congenital syphilis, according to a Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) report.

Prior to 2017, you could count the annual cases on one hand.

As long as syphilis is circulating in the community, “everybody’s at risk,” says Kellie Murphy (PGME ’98), a professor at Temerty Faculty of Medicine’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology.

Indeed, she cautions that thinking of any one group as having a higher risk may be misleading.

Many expecting parents are blindsided when they learn they’re infected because they may not have symptoms or they believed their partner was monogamous, says Professor Murphy.

Syphilis is known as the “Great Imitator” because its symptoms can easily be mistaken for other infections and conditions, complicating diagnosis in both adults and babies. One of Murphy’s patients saw four different doctors for a variety of symptoms — rash, mouth sores, vision problems — but only learned that her symptoms were related to syphilis when she got pregnant.

Congenital syphilis is almost entirely preventable, and treatment is highly effective. Experts say that seeing any cases signals a failure of health care systems to reach affected parents and babies.

National numbers reported by PHAC likely don’t capture the full toll because they only include confirmed cases within two years of a live birth.

Syphilis can cause miscarriage, and it’s estimated that roughly 40 per cent of babies delivered by parents with an untreated primary syphilis infection are stillborn or die soon after birth. Others may not be diagnosed until years later.

In Alberta alone, provincial figures show at least 170 cases of congenital syphilis and 35 deaths since the beginning of the outbreak in 2015.

Alberta and Manitoba together account for four in five confirmed cases of early congenital syphilis in Canada.

“To put it in perspective, the expected number of cases is zero,” says Ameeta Singh, a clinical professor in the Department of Medicine at the University of Alberta. “This is completely unacceptable to see in Canada.”

This is Alberta’s second syphilis resurgence since the early 2000s.

During the last outbreak, Professor Singh learned that every year, there were at least a hundred women delivering babies in Edmonton who received no prenatal care and likely missed crucial screening.

Not much has changed since then.

“It just seems to be on a different scale now,” says Singh. Then, as now, congenital syphilis was “really just the tip of the iceberg of a whole bunch of social problems that have come to a head,” says Singh.

In theory, routine screening during pregnancy should identify all expecting parents with untreated syphilis. The earlier they receive treatment, the less likely the infection will pass to the baby.

However, some people may become infected after testing negative or receiving treatment early in pregnancy, and clinicians may not think to test them again unless they have obvious symptoms or report risks such as drug use or sex work.

In other cases, health services may lose track of patients before they receive test results or finish a course of treatment. Or a patient’s information may not follow them to the hospital when they deliver.

While some provinces have introduced universal retesting for syphilis later in pregnancy, curbing congenital syphilis requires reaching beyond the walls of clinics and hospitals.

In Edmonton, that has meant developing programs to connect women experiencing homelessness with prenatal care, as well as providing non-judgmental housing with embedded health and social services for those who might be rejected from other programs.

“We realized that people were not coming to us,” Singh says, “so how could we go to them?”

Rapid testing for syphilis also holds promise.

“We’ve had health care staff doing rapid testing over the last two years in a number of different settings as part of a study, and we picked up a ridiculous number of cases,” Singh says.

However, the research team had to get a special exemption to use the rapid tests because Health Canada hasn’t approved them yet.

Outreach services are important because prenatal care may not be accessible to people who live in precarious situations — whether that’s due to poverty, unstable housing, mental illness, addictions, abuse at home, the long-term effects of residential schools or other challenges.

Other expecting parents may be wary of seeking health care because of discrimination or fear that their baby will be taken away, say experts.

All of these barriers disproportionately affect Indigenous people — in Alberta, three in five babies with congenital syphilis are born to First Nations mothers.

Most provinces only recently stopped the longstanding practice of health workers covertly issuing “birth alerts” for parents they deemed unfit — a practice that led to hundreds of newborns being taken into foster care, sometimes shortly after birth.

Singh attributes the success of programs that offer testing and treatment outside of the usual health care settings to the involvement of community health representatives — mostly Indigenous women who work alongside nurses to provide a range of support services including health education and promotion.

In Nunavut, investments in community health representatives have been linked to lower rates of congenital syphilis despite an increase in infections among adults.

At the Call Auntie Clinic in Toronto, Indigenous midwives and other clinicians work alongside community birth workers.

Cheryllee Bourgeois, a Métis midwife with the Call Auntie Clinic and Seventh Generation Midwives Toronto , had never seen a baby born with syphilis until last year. Then she saw three.

She says many people think of syphilis as an “old-timey kind of illness” — a sexually transmitted souvenir of the distant past before penicillin became widely available as a treatment in the 1940s.

Formerly a registered midwife and now practising under an exemption for Indigenous midwives, Bourgeois aims to act as a bridge between her patients and the health care system.

She has seen patients in encampments, hospitals, and community facilities where they are comfortable – making sure that their records are available wherever they go.

Respect for a patient’s self-determination is key, Bourgeois explains.

Sometimes, respect means taking the long view in a relationship with a patient and setting aside short-term clinical goals.

“I had a first visit with a client who was 12 weeks pregnant when I chatted about their history and that’s it — no other clinical thing,” Bourgeois recounts. “But what that does is set me up for the next time to take her blood pressure.”

If a client doesn’t want to see an obstetrician, Bourgeois collects the information the specialist needs so the records are ready if the client ends up going to the hospital.

She also develops “warm referral pathways” with trusted specialists in different settings who she can vouch will treat her patients with respect.

“It’s a very different experience for somebody to walk into a hospital with records on file, even if they’ve never been seen there, as opposed to coming in with the perception that they haven’t received any prenatal care,” Bourgeois says.

The goal is to complement, not compete with, mainstream care, she adds.

“You need to have the large hospitals with the capability to do an ultrasound and take your blood all in one place. But that can’t be the only thing,” Bourgeois says. “You always need to ask yourself, ‘Who are we not seeing? And why are we not seeing them?’”

Professor Suzanne Shoush (PGME ’10), a First Nations/Black physician at the Call Auntie Clinic and the Indigenous Health Faculty Lead at Temerty Medicine’s Department of Family and Community Medicine, says that shifting more care to the community is a “huge piece of the solution” in improving access for people whose needs aren’t being met by mainstream services.

That includes shifting resources to value community expertise alongside clinical expertise.

“Those are the people who are trusted by the patients we serve, and it’s that trust that’s important — not necessarily a degree from a colonial institution,” says Shoush.

Health care funding is often distributed unevenly to certain parts of the system, Shoush notes. For example, most primary care funding goes to family doctors, yet most Indigenous people don’t have one.

Meanwhile, Shoush says, community collaboration requires humility, flexibility, and a willingness to think outside of the medical hierarchies that can be frustrating for clinicians.

“There’s truly a baseline level of exhaustion in medicine,” Shoush explains, which she says can make it difficult to deviate from the doctor-knows-best approach to care.

Ultimately, improving access is not about “figuring out how to get a patient to attend an appointment in a way that works for the health system,” she says.

“You conform to what works for them.”

By Heather McCall

The state of any creature’s physical being can be traced back to a single moment. For sexually reproducing organisms, such as humans, it’s the moment a sperm fertilizes an egg. In that instant, the blueprint is created for the organism’s physical development and health.

This thought struck Emma Campbell (BSc ’20) during a lesson on fetal development, and it was a revelation of sorts. It was March 2020, and Campbell was in her final year of earning an undergraduate life sciences degree. She was sitting in an anatomy class in the Medical Sciences Building and contemplating future career options. Until that moment, she imagined continuing her studies in either molecular genetics or pathobiology, most likely focusing on cancer research. Then everything changed.

“I realized that when it comes to genetics and disease, everything starts with fetal development,” she says. “I knew at that point that if I wanted to contribute to human health through lab work, that’s where I could have real impact.” It was the start of a different educational direction. In early 2021, Campbell applied to a new program at the Temerty Faculty of Medicine and is now completing her first year of its Master of Health Science (MHSc) in Laboratory Medicine, Clinical Embryology Field.

Launched in 2020, the Clinical Embryology Field program is a full-time, two-year professional graduate program offered by Temerty Medicine’s Departments of Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology (LMP), and Obstetrics and Gynaecology (OBGYN). The program teaches students both the theoretical and applied science of embryology, which is the study of gametes (sex cells) and fertilization, and the development of embryos and fetuses. Students work toward becoming clinical embryologists.

These professionals typically work in a hospital or fertility clinic. Clinical embryologists are responsible for the lab work related to the development of healthy embryos used in assisted reproduction technologies, the most common being in vitro fertilization (IVF). When it comes to trained clinical embryologists in Canada, demand is outpacing supply.

“Many of the clinical embryologists working in the field will be retiring over the next 10 years, and there hasn’t been much in the way of succession planning,” says Scot Hamilton, an assistant professor in Temerty Medicine’s LMP department and a clinical embryologist at Mount Sinai Fertility.

Until recently, most clinical embryologists in Canada learned their trade on the job through apprenticeship programs, says Professor Hamilton. They would get hired at clinics as medical technologists trained in lab procedures but without embryology education, says Hamilton, or they’d be hired as university graduates with cellular biology backgrounds but little in the way of lab experience.

The Temerty Medicine program is unique in that it teaches students who have a solid foundation in biology everything about embryology, including crucial lab skills, he says. Hamilton joined the program development team 4 years ago to help establish the curriculum.

At the time, Heather Shapiro (PGME ’92), who is now an associate professor in Temerty Medicine’s OBGYN and LMP departments, and Theodore Brown, now a professor in the LMP and OBGYN departments, were finalizing the program. “Before we launched the MHSc, if you wanted to gain this level of education and training in embryology you’d have to go to Australia,” says Hamilton.

The Clinical Embryology program currently accepts only five students per year, although Hamilton hopes they will be able to increase capacity in the near future. It’s structured so that first-year students gain a foundational understanding of the science, history and ethics of embryology. In the second year, students do hands-on training in the Clinical Embryology Skills Development Laboratory.

The state-of-the-art simulated clinical teaching laboratory is the first of its kind in Canada and was created specifically to support the program. It opened in the Medical Sciences Building in September 2021 with support from The Fertility Partners, a network of Canadian fertility clinics, and EMD Serono. In the lab, students work with animal gametes to learn the skills required to yield a healthy embryo.

Campbell looks forward to applying her knowledge in the lab next year and working in a fertility clinic after she graduates.

“I definitely want to get a job in the field,” she says. “The more I learn about IVF, the more interested I am in what it offers.” ●

By Emily Kulin

Until recently, women with cervical cancer in western Kenya had uncertain prospects of receiving effective treatment. Several factors contributed to this situation, including a lack of screening programs, limited familiarity with and access to treatments, and — critically — a near-complete shortage of trained gynaecological oncologists. In 2008, the country had only one gynaecological oncologist serving its population of 40 million people.

“With the rising cancer burden, there was a huge need to train more physicians and surgeons specialized to meet the needs of so many women with these types of cancer,” says Benjamin Odongo Elly, a senior lecturer in the Kenyatta University Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology and former president of the Kenya Obstetrical and Gynaecological Society.

Barry Rosen saw the situation first-hand in 2008 while attending clinical rounds in Eldoret, Kenya. “Patients were presenting with very advanced cancers, and there wasn’t much local physicians could do except offer palliative care,” says Rosen, an adjunct professor in the Temerty Faculty of Medicine’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology and the section head of gynaecological oncology at Beaumont Health in Michigan. “It was deeply troubling.”

Faculty members at Moi University and Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital, including gynaecologists Peter Itsura and Omenge Orang’o, were keen to bring about change.

They saw a path forward in an existing consortium: the Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare (AMPATH).Begun in 1990 as a collaboration between Moi and Indiana University, AMPATH has grown into a global partnership. It links North American and Kenyan academic institutions to develop a system of sustainable health care in western Kenya.

In 2007, the University of Toronto Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology joined AMPATH as the lead North American member focused on women’s and reproductive health.

“Our relationship with Moi University, through AMPATH, exists to serve the needs of the local community. The idea is to develop the depth of clinical care and expertise with our local partners as the lead,” says Rachel Spitzer (PGME ’06, ’07), vice-chair of global women’s health and advocacy in Temerty Medicine’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology.

Rosen was one of the first U of T faculty members to collaborate with Itsura, Orang’o and other colleagues at Moi through the AMPATH consortium.

Together, they set up a gynaecological oncology clinic and developed a cervical cancer screening program delivered through AMPATH’s existing HIV and AIDS clinics in western Kenya.

Then, in 2011, the group developed a landmark two-year clinical fellowship curriculum in gynaecological oncology.

It would become the first subspecialty training program in Moi University’s history — and the first gynaecological oncology training program in sub-Saharan Africa outside of South Africa. North American specialists were recruited to serve as the program’s faculty and provide on-site training to Kenyan fellows, but covering the costs associated with their travel and living expenses were key to the program’s success.

The fellows also needed to come to U of T and its partner hospitals for specialized surgical and oncologic training — and this required more funding.

These fellowships would not be running, would not be possible, without the Kimel Foundation’s support

Enter Warren Kimel, the chief executive officer of Fabricland, Canada’s largest retail chain of fabric stores. “Warren and I went to high school together and were roommates in university. We’ve stayed close,” says Rosen. “He ended up going into the business world, where he had tremendous success.”

“Barry told me what he was seeing in Kenya,” says Kimel. “He connected the work they were doing on training with how it could ultimately help save lives.” With philanthropic support from the Warren and Debbie Kimel Family Foundation, the fellowship program was in full flight.

Itsura and O’rango became the first physicians to graduate from the gynaecological oncology fellowship in 2014. They were followed by a further six graduates over the next seven years, including Elly.

Many graduates have stayed at Moi to care for patients and help train future fellows, while others moved to different parts of western Kenya and eastern Africa where they have set up additional gynaecological oncology clinics and fellowship programs. One such alumni-led fellowship program in Uganda has already trained four additional gynaecological oncologists.

Following the fellowship’s success, the initiative was expanded in 2019 to include a similar training program for maternal-fetal health specialists, also funded by the Kimel Family Foundation.

This new program seeks to reduce maternal mortality, provide safe abortion care and improve outcomes for pregnant Kenyans with heart disease, hypertension or diabetes. As well, it strives to reduce rates of preterm birth and fetal growth restriction.

“These fellowships would not be running, would not be possible, without the Kimel Foundation’s support,” says Spitzer. “We’re very grateful for this opportunity. This is truly transformative work.”

For Elly, the learning experience has been momentous. “The subspecialty training has empowered me to provide advice that will shape health care policy and provide sustainable expertise for women diagnosed with a gynaecological cancer,” he says. ●

In December 1969, a group of students from Kimberley Public School visited a baby found abandoned in a parking lot, at what was then known as St. Joseph’s Hospital.

The moment a child is born to Lynn Ruminski via C-section at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, in fall 2021.

In 1928, Women’s College Hospital student nurse Peaches Smith cares for a newborn.

In this photo from 1977, Rebecca Awaviapik and her son Carson chat with a friend, Suvinai Mikijuk.