Exploring the lifelong effects of an early arrival

By Meagan Gillmore

I always debate if I should mention my birth on health forms that ask for my medical history. As I stare, pen raised above the blank line, I ask what would a medical professional learn from reading the words “born prematurely”? How do the first days of my life impact the decades that followed?

I bend close to the health form, steady my good eye as best as I can, and after “medical history” I write, “None.” The medical establishment might beg to differ. In some respects, they’re right. Premature birth, defined by the World Health Organization as any birth before 37 weeks gestation, is an important health concern for children, parents and their broader communities.

Worldwide, premature birth is a leading cause of infant and child disability and death. About eight per cent of births in Canada occur prematurely. At its most basic level, premature birth is a stark reminder that all humans will die. And, despite our efforts to ignore or deny it, we have less control over our lives than we think.

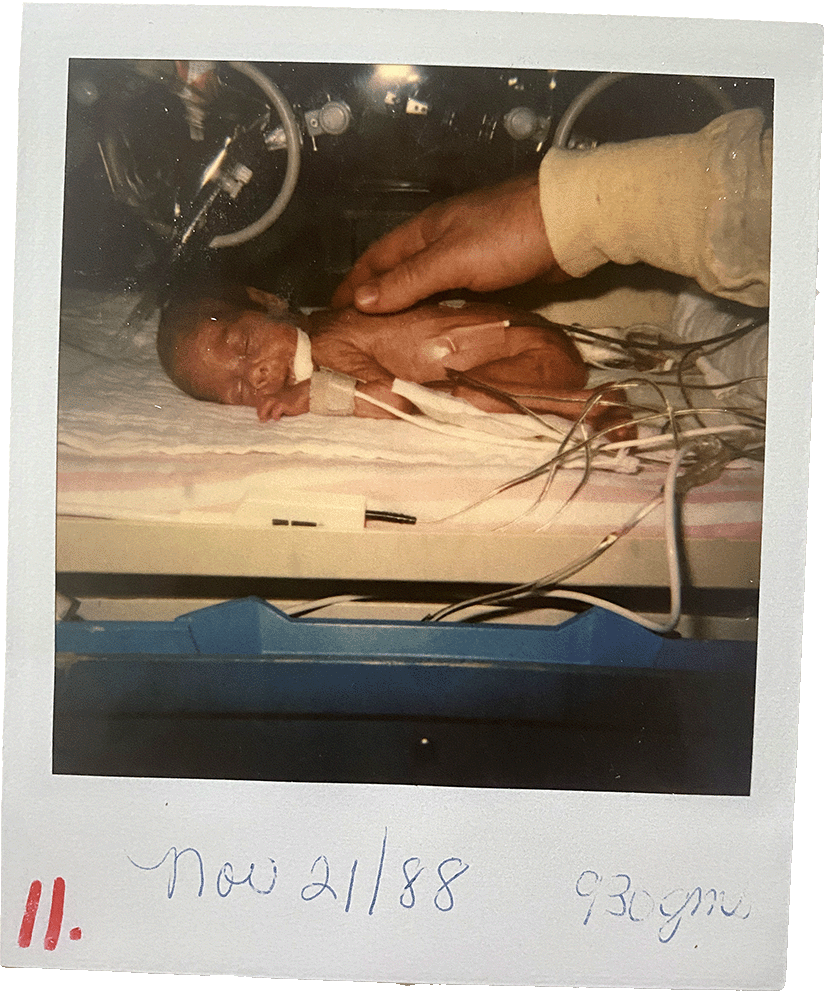

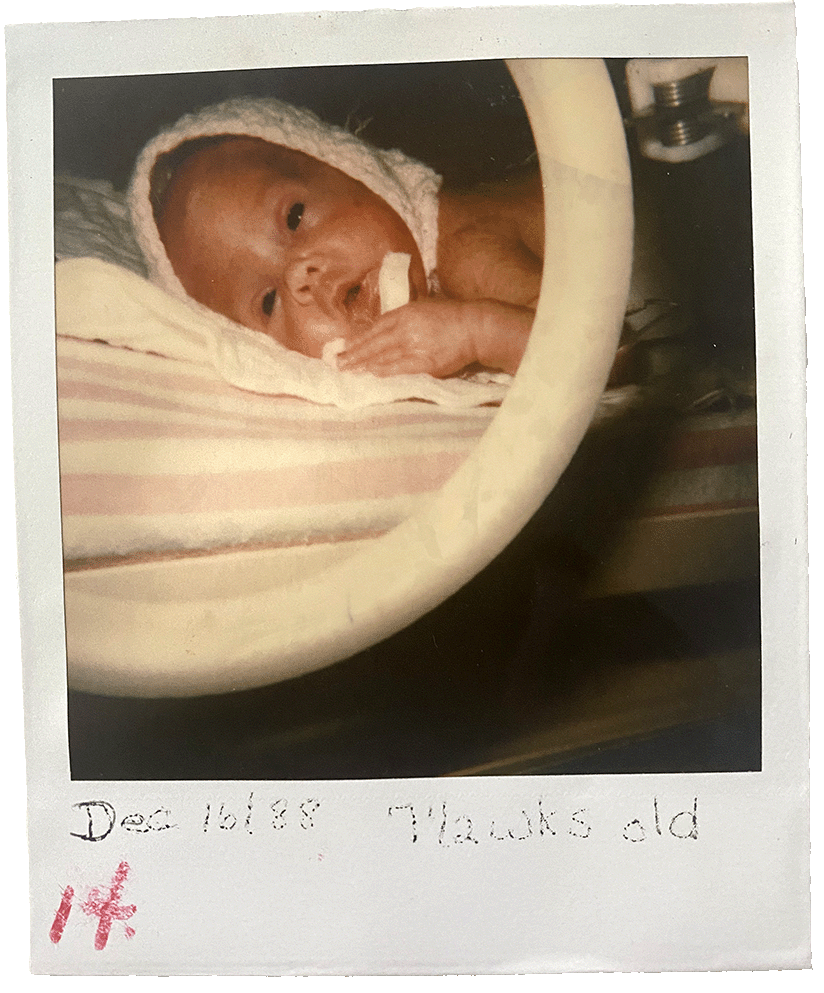

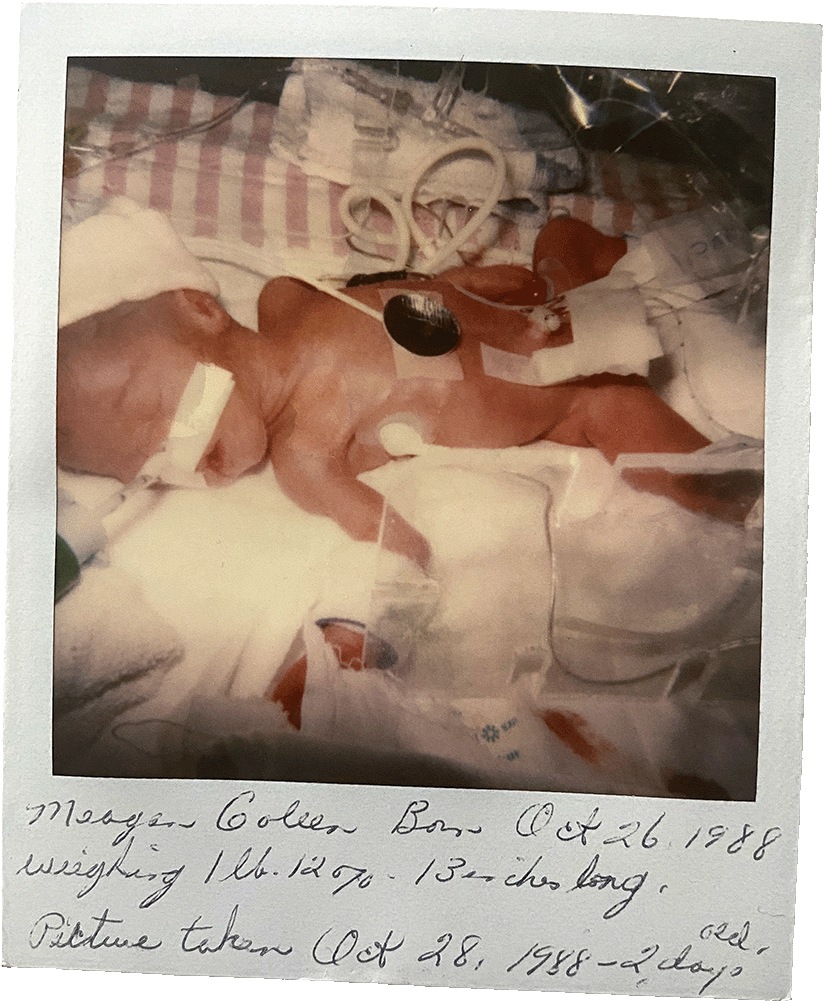

I arrived via emergency caesarian section on October 26, 1988, at 27 weeks. I weighed about 1 pound and 12.5 ounces, or just over 800 grams, lighter than a large bag of candy rockets. I stayed in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) for about three months, until early 1989. My father’s birthday is on January 22 and, as the story goes, I was home for that.

I don’t remember anything about my time in the NICU. I view the girl in the Polaroid photos that the nurses took of me as a stranger. Intellectually, I know she is me and that my personality was forming even as my body and organs finished developing underneath wires and gauze. But I don’t typically consider those months as pivotal in my life.

That is, until I am asked to declare my income. Then, the economic reality of surviving a premature birth becomes clear. Like many premature infants who survive the NICU, I left with a permanent, uncorrectable disability. I have retinopathy of

prematurity, an eye condition I argue begins in the best way possible — with being alive.

I am legally blind. I don’t read braille, but I can’t decipher facial expressions or see street signs. Driving gives me recurring, sweat-inducing nightmares. Adults with disabilities are significantly more likely to struggle finding full-time employment, and I haven’t beaten those odds.

Once, a government-funded ventilator helped me breathe; an incubator was my cradle. Years later, much of my living expenses as a young adult were covered — partially, at least — by a meagre government disability pension. Despite remembering nothing about my first months of life, I’m fascinated by the broader cultural and scientific curiosity surrounding preemies.

Some descriptions of preemies’ lives focus on the NICUs, where alien-looking children with translucent skin spend their first days, weeks or months in a web of tubes, sleeping while monitors whirl and, as is often repeated, defying the odds.

In many cases, these lives are viewed economically: What, inquiring minds ask, does care for these lives cost?

Medically, it’s complicated.

A study — “The economic burden of prematurity in Canada” — found that premature infants collectively have a national cost of $587.1 million in their first 10 years of life, both directly through medical costs or indirectly through the lost productivity of their caregivers. The study further estimates that in their first decade, a child born in Canada before 28 weeks costs $67,467 to care for, including direct medical costs and parental out-of-pocket expenses.

There seems to be an unspoken question lingering in the research: Who is going to carry these costs? In 2020, a study published in Seminars in Fetal & Neonatal Medicine described the physical, economic and social well-being of young adults born prematurely.

Some descriptions fit me. I receive social assistance, although in lower amounts when my employment increases. I’m unmarried and childless. I’ve never had a romantic relationship.

If I do have children, research from U of T’s Lesley A. Tarasoff (PhD ’18) indicates that because I have a sensory disability, my children have a greater chance of being born prematurely or, at least, of having a low birth weight.

Because of the high incidence of disability among premature infants, my potential children may also experience the poverty often associated with having a disability.

However, when older premature children describe their well-being, results aren’t all dispiriting. Some of us hesitate to even assign negative qualities to our disabilities.

My time in a hospital unit doesn’t tell me I’m a burden; it shows me I am loved

One 2022 study reports that, despite struggling to read newspapers or recognize friends from across the street, 19-year-olds with retinopathy of prematurity say they have good visual function.

Research also suggests that extreme prematurity may contribute to a lower income and the lack of romantic relationships — two often difficult aspects of my life. The study, however, warns against describing the lives of premature infants in bleak, economic terms. It notes that “negative effects of extreme prematurity” are limited to a small subgroup. It concludes, “The value of life should not be measured purely in economic terms.”

It makes me sad that this truth needs to be emphasized.

If preemies’ lives are burdens, it’s not because they’re heavy. It’s because current social structures are often not strong

enough to help people impacted by prematurity to fully live their lives. As a child, I was hailed a survivor. But the supports of an NICU don’t continue outside of hospitals. As a young adult, I often felt that my life was reduced to just surviving — and no one cheered for that.

There is a psychological weight that comes with belonging to a group of people whose lives are constantly being monitored and measured. For me, there is a heaviness of being a tiny, early baby; it’s the burden of sharing what I was given in the NICU. Ultimately, my time in a hospital unit doesn’t tell me I’m a burden; it shows me I am loved.

I know I am loved because hundreds of people prayed my mother and me through our time in the hospital, and because families fed my father, brother and sister when my mother and I were in the hospital. I know I’m loved by the outfits my maternal grandmother made, patterned after doll clothes so I’d have something that actually fit.

I know it by the desks my maternal grandfather made for me as a child so I could more easily see my schoolbooks. I know I am precious by the awe and gratitude in my paternal grandfather’s voice as he shared the story about how, after seeing my tiny body in an incubator, a nurse rebuked him for suggesting to my grandmother that I wouldn’t survive.

Years later, my grandmother turned to me in the middle of a relative’s discourse about the cost of premature babies and sternly reminded me that my parents were not in debt because of my infancy. And I know it every time I hold a premature baby and remind them that strength often comes in being held.

At its most basic level, premature birth is a stark reminder that while we have less control over our lives than we like to think we do, we are valued more than we know. ●